Reimagining an Earth-centric and child-centric education

Specially written for Vikalp Sangam

On the Drumstick tree dozens of Lappet moth caterpillars had begun to descend from the foliage. Their furry bodies draped its trunk. Tender bark exfoliated with their feeding. I was accompanying a group of children to the animal shed, at the Songlines Farm School. Songlines is an alternative educational space I am part of running under Abacus Montessori School, where children and educators live and learn on a farm, with the natural environment. It is located in the small village of Vellaputhur, in the district of Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu. The monsoon was retreating, and the dense December mist would veil every dawn for several more days.

Larvae throw a unique challenge to language. Lappet caterpillars physiologically lack a gender till they metamorphose into moths. For the period of their larval lives they are non-binary creatures and their physicality ‘trans’cends our commonly held gender notions. Let us for a moment suppose – if we had to address the caterpillar, how would we, while also treating it as an alive, animate creation? What pronoun would we use to describe its activities on the Drumstick tree? She, he, it – all fall short. ‘They’, ‘them’, ‘Ze’, Zir’ are now coming into use. The bryologist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer has proposed the words ‘ki’ and ‘kin’, singular and plural respectively, as gender-neutral more-than-human pronouns, for trees, moss, mountains and others we’d like to speak of, ascribing animacy to. ‘Ki’ is from Potawatomi, a native American language. ‘Kin’ is from English, ringing with kinship. They happen to be phonetically related words.

“Ki is crawling down the trunk to pupate in the soil”

“Kin are more in number on the shady side of the tree”

I feel a dormant part of my mind shifting in its sleep when I speak these sentences. They stretch my mind in an unfamiliar direction, though a strangely intimate one. Here is a new portal of greeting, speaking, meaning-making when I meet caterpillars, trees and millipedes.

Across the line of Drumstick trees, in the vegetable garden, I would later do an exercise with children, as another experiment in shifting perception.

Children at Songlines transplanting paddy

Some weeks later. Children strolled among the vegetable plants with iron pans to harvest Lady’s finger, Brinjal and Azuki beans. I crouched by some bean plants which were swathed with Aphids, to photograph some event which may occur amongst their gatherings. Golden backed Ants (Camponotus sericeus) farmed them with their antennae-tapping. Ants have been livestock-keepers for many millions of years before humans. Aphids in turn secrete sugar solution for the security services provided by the ants. Leaf petioles held fresh frothy spawn of froghoppers. I turned over bean leaves one by one, looking for any interesting insect-world occurrence, and the underside of one leaf offered me a radically new idea to engage children.

In the spaces between the veins were Aphid patches. Two Zig-zag Ladybird Beetles, staunchly aphidophagous creatures, were lazily eating them from one end. In a while an Ant came to check on its bug-herd, and charged open-mandibled at the raiding beetles, both of whom flew away as soon as the leaf shook with the ant’s arrival. Within a square-inch of space I had seen a whole web of ecological relationships, between four beings.

Let me list them –

Aphid on the Bean plant – Parasitism

Ladybird Beetle and Bean plant – Mutualism

Beetles eating Aphids – Predation

Ant and Beetles – Competition

Aphids and Ant –Mutualism

Bean plant and Ant – Commensalism

An entire ecological web under a bean leaf

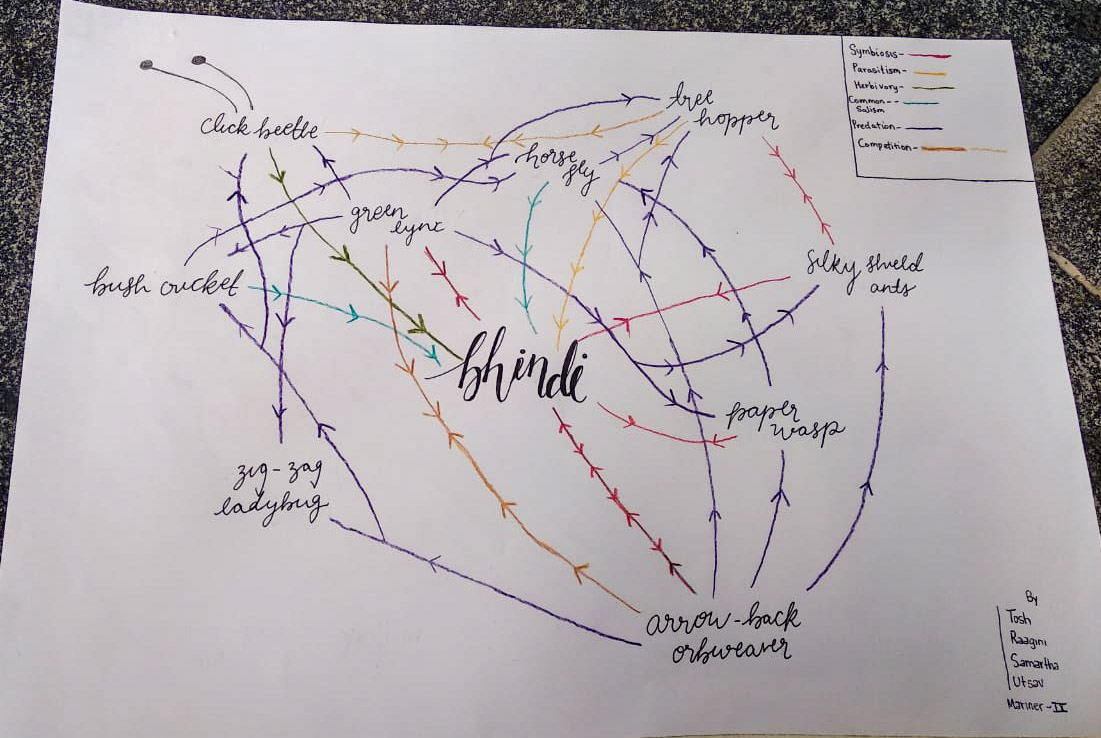

In a few days, I sent groups of 9th grade children around the farm, each assigned a specific crop or plant – Paddy, Brinjal, Cluster Beans, etc. They were to observe the life on them, make observations, use field guides to identify the species they saw and make a ‘Relationship Web’. In mapping a relationship-web, children spread the names of the organisms they see, on paper. They then map six different ecological relationships (mutualism, parasitism, competition, predation, commensalism, and herbivory), each drawn with a different colour. Each creature is linked to every other one, through at least one of the colours – with a legend below as to which colour indicates what relationship. This is in contrast to a food-web, which is taught as an important concept in biology – a construct which portrays ecosystems as hierarchical, linear, and somewhat crudely communicating to children that organisms merely eat each other in nature – a structure somewhat reflective of our own linear extractive models of economy, society.

A Relationship-web maps an ecosystem more vividly and accurately. It is non-linear, complex, non-hierarchical and lends to many ways of seeing and comprehension. Children come up with composite and colourful maps of the microhabitat they have studied. You could start anywhere on it and follow it around in various ways, each an equally valid story of interactions and energy flow.

A relationship web mapped by children on the Bhindi/Lady’s Finger plant

Once the activity is over and the Relationship-webs are presented by each group, several reflections are pursued.

What were some new learnings and un-learnings during the activity? Which relationships are the most frequently noted in my web and why? How do soil, water, and air flow in it, animate it? How do we participate in this web?

With teachers and older students, I have pursued or been posed with some deeper questions which have sparked off other tangents of conversation –

“If democracy is a matter of shared beliefs, then I believe in the democracy of species”

– Robin Wall Kimmerer.

A relationship web charts what could be called an ‘inter-species democracy’ which is alive in natural ecosystems. Where extractive energy flows are balanced with counter flows to it. And where one can see interdependence, diversity, and plurality at work.

“When you see this paper, do you see the clouds?” – Thich Nhat Hahn

When we see life forms, do we see them as separate objects or do we also see their relatedness? How easily do we perceive relatedness?

What social constructs are reflected in other concepts and subjects taught in school? Do we want to reimagine, restructure them?

______________________________________________________________________

In her essay “Perceiving how we perceive”, educator Seetha Ananthasivan speaks about two different kinds of perception – object perception and process perception. She says, “a major preoccupation in nursery and primary education is on learning the names of objects.”Little is done to allow the child to discover the connected and hidden realities of these isolated objects. For instance, is a child encouraged to think, ask a question of a water bottle – where it came from, how it was made, where it will go after its use? This is process perception. In the materials we use, food we eat, clothes we wear, do we perceive beyond their separate forms?

We could say that the culture of consumerism, even the politics of capitalism thrives on object perception. Violence, deeply hidden and structural, is distanced from the products on their sanitized shelves. They dote on anaesthetized eyes which don’t and won’t see beyond them.

As somebody working at the intersection of education and conservation, I am interested in understanding if and how ecological loss affects the richness, depth, and diversity of our perception – especially of children who have come into the world during this period. Also, are we to pass on the same model of education we went through, in the era in which they’ve entered this planet?

In my experience as a teacher, young children have a natural familiarity and curiosity for parks, fields, beaches, bird sanctuaries – wildernesses. In little time they feel at home – somehow part of the living-systems themselves. This capacity of kinship and openness to the trees, birds, insects, and soil diminishes if such experiences are not created when they are young. Children are deprived from many ways of seeing, thinking, and learning when schooling is divorced from the natural world. Visionary educators like Maria Montessori and J.Krishnamurti have emphasised this in their teachings. In her concept of ‘Erd-Kinder’ Montessori stresses upon the importance of adolescent children growing in a farm-school, working with the land, growing their own food and being in touch with the landscape. She explains how this is a necessity for the developmental needs of children at this age. Richard Louv braids the wild and the wellbeing of the child intimately in his seminal book ‘Last Child in the Woods’. He emphatically says that “if we are to save the environment, we must also save an endangered indicator species – the child in nature”. Children and nature have a reciprocal relationship in protecting each other.

Children studying butterflies at Songlines

Work by psychologist Gail F. Melson opens up how contact with other forms of life is important in all aspects of child development – cognitive, social, emotional, and moral. She, like others, attributes this to the fact that nature is the most complex and composite learning environment we can provide a child, and hence an un-substitutable one.

I am continually astonished by how a well-planned activity in Kotturpuram Tree Park or Adyar Poonga or Vedanthangal Bird Sanctuary, or at our arboretum at Songlines is inclusive and supportive of a variety of learning styles. Time and again, children labelled as ‘challenged’ by the linear yardsticks within the cinderblocks of classrooms, are able to express and enjoy themselves through their unique capacities and on their own terms, in living learning environments.

I am also keen on exploring how we can bring ecological principles into our schools and learning environments, just as we bring learning environments into ecological spaces. A fundamental aspect to any ecosystem is ‘diversity’. As Colin Baker has put it “In the language of ecology, the strongest ecosystems are those that are the most diverse.” In a single ecosystem we notice that there exists rich perceptual diversity. The Ghost Crab which sees the horizon as a full circle with its periscope-like cylindrical eyes. The strange Chiton, an unearthly mollusc, which sees in magnetic field lines and has an astonishing acumen for navigating the seabed. The Sea-Eagle which rides rising thermals and sees in heat. The mangrove trees which live by the tidal rhythm, stand on stilts, and speak with each other through fungal networks under the ground. The Blue button, which looks like a little jellyfish but is a colony of creatures working together like an organism, a puzzle between singular and plural. The Magpie Robin which makes new music each morning, who never sings the same song twice. The Octopus which speaks through colour. The Sea snake which paints its world through smell. Each creature has its own distinct perceptual field. Each sees the world so differently. Yet this diverse mosaic of perceptual fields, roles, and abilities, woven together by sand, air, sea and sky – form a webwork of numerous interdependent lives and a thriving and resilient intertidal habitat.

Can children’s learning environments be an ecosystem? A place inclusive of diversity – inclusive of all kinds of intelligences, capacities, cognitions – which makes it a rich habitat rooted in the place it is in. Such an ecology of learning spaces would be both Earth-centric and child-centric, and these, I think, are urgently needed now for children and the planet.

The mainstream education system is both unnatural and detrimental for this Earth-child complex we have been discussing. It is often described as ‘factory-schooling’ as it is rooted in mono-culturing and homogenizing children’s minds and aspirations. It is also a fundamental driving force for the economic system and the destructive model of ‘development’, both of which are the primary propellers of climate crisis, biodiversity loss and the social injustice we are witnessing today. As Carol Black says, the conventional education system functions such that children are “molded and fashioned like any other industrial raw material into a predetermined finished product”. It was devised for a dream of colonial industrial utopia. And I agree with David Brooks who describes that “its main activity is downloading content into students’ minds, with success or failure measured by standardized tests”. Those whose capabilities lie in the vast ‘outside’ of the system’s purview are ‘failed’, creating what Manish Jain calls a “new kind of academic caste hierarchy” and a “crime against humanity”. We treat children like inert media, passive recipients to be shaped into products for society – consumer beings. Often, their growth and blossoming, if at all, is in spite of schooling. Notably and not surprisingly, such education treats ecological literacy as adjunct, optional or unnecessary portions to be omitted.

The current schooling system also devalues diverse kinds of cognition. I immediately think of children I have interacted with along the Elliot’s beach over the years, who belong to the local fishing communities. They have a profound knowledge of the coast and seas. They are innately aware of the longshore currents, tides and can plainly predict weather. I can do none of these, despite walking these shores for over two decades. Or consider the children of the Kattunayakan tribes of the Nilgiris who can understand and track bees and hold vast spatial maps of the forest in their minds. Though modern schooling marginalizes these communities and seeks to make them ‘literate’, their embodied ecological literacy is astounding and is something no mainstream school has achieved. For the indigenous and Adivasi communities of India, education, and the ideals it imposes, has often been a form of acculturation, by de-basing their knowledge-systems. Younger generations are no longer valuing them and are no longer bearers of their eco-cultural wisdom.

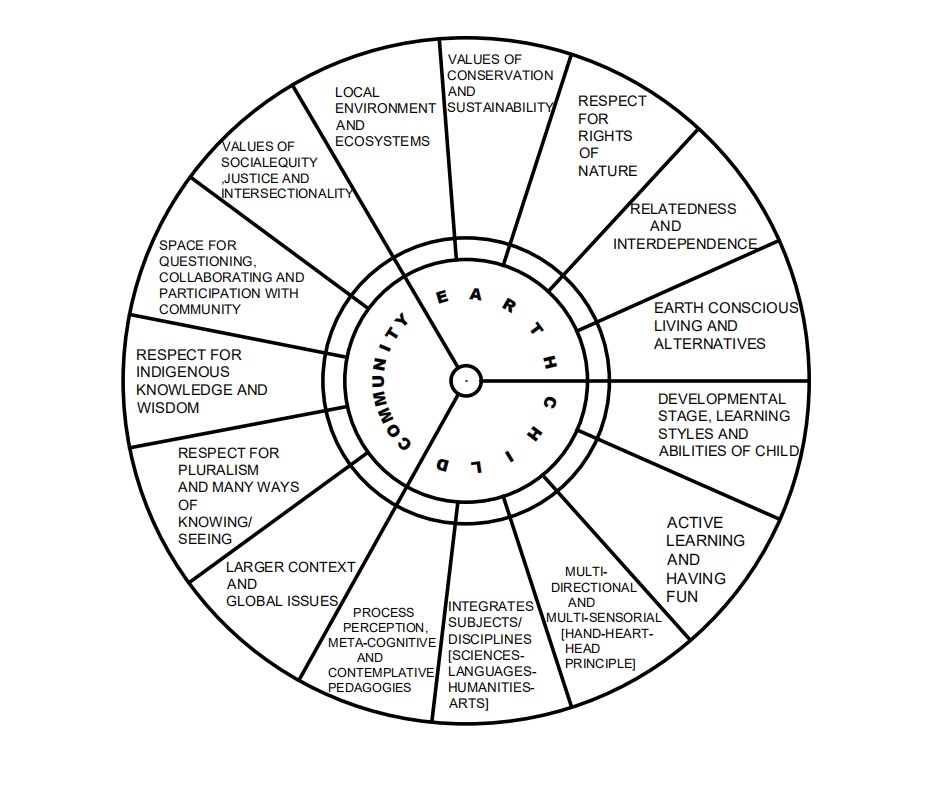

A counter current to this form and definition of education has been emerging -through schools, colleges, and other institutions and movements whose core principles draw from ecological values, democratic values, and inclusivity of children – across learning styles, cognitions, and contexts. The unschooling and home-schooling movements have had an important role to play in this too. For my own work as a nature-educator, my visits to and interactions with such alternate schools have been deeply formative. They include Pathashaala, Bhoomi College, Marudham school, Shikshantar, SECMOL, Barefoot College, Swaraj University, Wild Shaale among others. And for the curriculum and activities I plan for children at Songlines, I have made for myself a ‘Songlines Wheel’ based on these learnings. This is the value wheel which I draw upon, to keep me grounded.

The Songlines wheel has at its centre Child, Earth, and Community. And its spokes hold various values under each, which guide the teacher. The wheel is the basis of an ‘Un-syllabus’ we are evolving – a participative, spacious, and context-based curriculum based on these values.

Here are some of its broad guidelines –

Bottom-up pedagogy – this means that the context, place, children, and their energies and capacities decide the curriculum. The curriculum is place-based. As opposed to the mainstream curriculum, which is top-down and sets a single rigid syllabus for everybody regardless of these diversities of contexts.

Conscious of content and process – this means that ‘what’ is being learnt or facilitated and ‘how’ it is done are given equal thought, time and effort. Conventional syllabi ignore processes and impose purely content.

Active learning –This is where children are active part-takers in the planning and learning process and have space to direct it and shape it.

Plurality – This has multiple implications. One is that these learning spaces normalize all kinds of learners and are inclusive of learner-diversity. Second is that lessons involve the head, hand, and heart and blur the artificial distinctions between sciences, arts, languages, and humanities, leaving no child feeling excluded. Third is that learning spaces are multidirectional – wherein learning happens along various trajectories, not just in the uni-direction of teacher-to-student. It also means that it’s a horizontal and poly-vocal space – where all voices speak and are listened to.

Values of Social and environmental justice– This means that rights of people and nature are respected and need protection for a just, egalitarian, and healthy community. Citizenship education is an important part of this where children learn their laws, rights and means to actively participate and partake in society.

The Songlines Wheel of Values

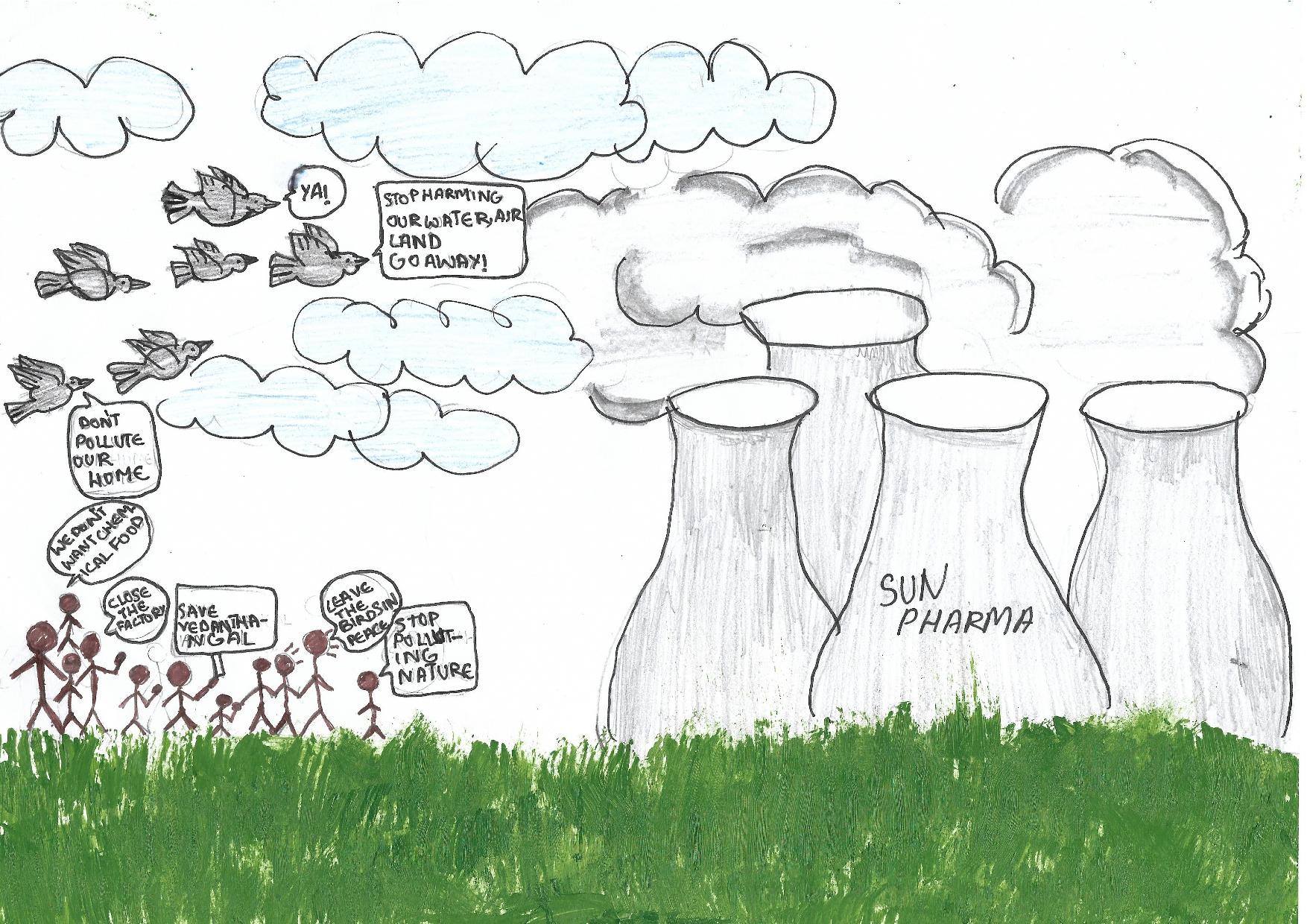

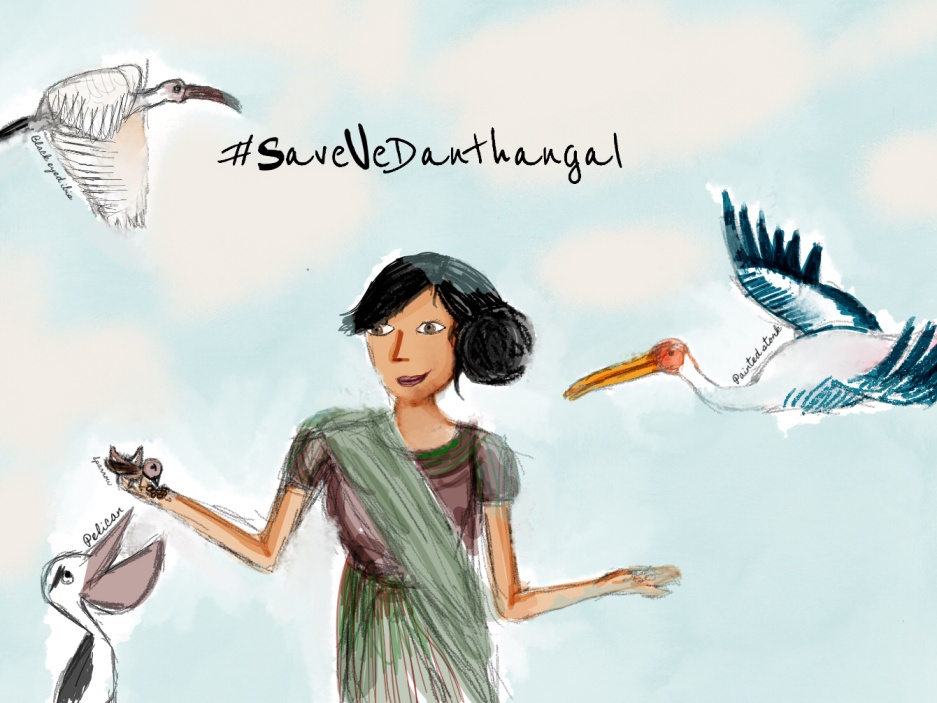

With the Covid lockdown, we had to take our farm-school to the virtual medium and it was at first a challenge to envision such a programme through a digital screen. Just then the Tamil Nadu state government announced the denotification of a significant part of Vedanthangal Bird Sanctuary – a place all the classes have visited, to watch birds and understand this lake’s rare example of community conservation. Our first module was to research about this issue and make campaign-art for Vedanthangal. The children’s work depicting their bond with the bird sanctuary and asking it to be saved, inspired many more schools after print media covered it. It incited numerous more voices to stand up for the cause. (Read Children Make Art to Save Vedanthangal Bird Sanctuary)

Following this module, some classes studied and illustrated the life-arc of various waste or unused materials at home and did upcycling projects with them. These came out to be cycle-tire clocks to a school bag stitched from outgrown jeans to toy-sets from cardboard to coconut-shell hand sanitizers. Other classes conducted ‘water audits’ in their homes, and researched and presented on various traditional water conservation systems in India. The lockdown had given us a strange opportunity to find other paths of learning and engagement, which, ‘unconfined’, we would not have thought of.

Through a subsequent module, the children became ‘Young Journalists’. Small groups reached out to various experts, naturalists, environmentalists, local people, government officers, etc. and conducted interviews about current environmental issues, and shared their findings with the larger group. And presently the older students are making a place-based, illustrated alphabet book for the primary school children (ages 2 to 6). A for Adyar river, B for Banyan, C for Coucal, D for Damselfly and so on. Words these young children can find, see, touch, enter and directly sensorially connect with in their school campus, around their homes and in the local landscape.

Art work by Songlines children for the Save Vedanthangal campaign