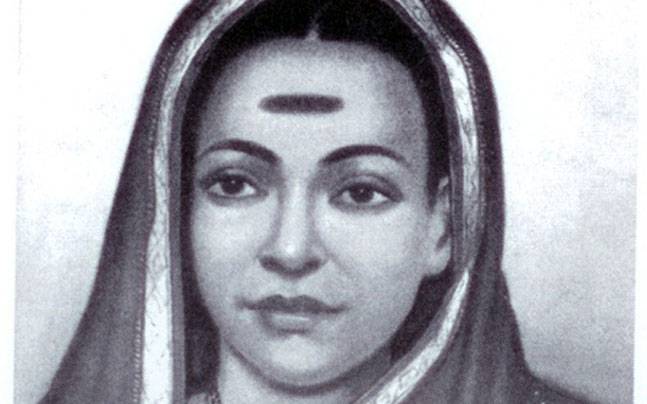

A leading social reformer Savitribai Phule is hailed for her contribution in the field of education. Savitribai was a crusader for women empowerment as she broke all stereotypes and spent her life promoting the noble cause of women’s education. The deprived of India’s exclusion was made to be a slave for thousands of years. Savitribai Phule has made education the biggest weapon of freedom from slavery.

Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule were a formidable team, their ultimate aim the unity of all oppressed communities. They were the first in modern India to launch a full-blown attack on the Brahminic casteist framework of society. In time they also included Adivasis and Muslims, and fought hard for their emancipation as well.

Savitribai was the means through which Jyotirao realised his vision. She, a woman who had seen poverty, caste discrimination and life without education, was the perfect role model for her students. It was because of her powerful influence as a teacher that one of her Bahujan students, eleven-year-old Muktabai, wrote a powerful essay that was published in Dyanodaya, a popular Bombay-based newspaper. She wrote, “Formerly, we were buried alive in the foundations of buildings… we were not allowed to read and write…God has bestowed on us the rule of the British and our grievances are redressed. Nobody harasses us now. Nobody hangs us. Nobody buries us alive…”

Another student, a boy named Mahadu Waghole, wrote about the relationship between Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule: “If she saw tattered clothes on the body of poor women, she would give them saris from her own house. Due to this, their expenses rose. Tatya (Jyotirao) would sometimes say to her, one should not spend so much. To this, she would smile and ask, what do we have to take with us when we die? Tatya would sit quietly for some time after this as he had no response to the question. They loved each other immensely.” Even though the Phules were constantly engaged in making others’ lives better, Savitribai took great care of Jyotirao Phule’s health and personally cooked all his meals.

Their relationship was based on respect for each other’s individual identities, which is why it survived the toughest of times, particularly their failure to conceive a child. Jyotirao was under a lot of pressure from his family to remarry for the sake of an offspring but he stayed committed to Savitribai. He wrote: “If a pair has no child, it would be unkind to charge a woman with barrenness. It might be the husband who was unproductive. In that case if a woman went in for a second husband how would her husband take it? Would he not feel insulted and humiliated? It is a cruel practice for a man to marry a second time because he had no issues from his wife.” These were radical thoughts for that time.

Much later, the Phules adopted a son and raised him as their own. Jyotirao had rescued and brought home a young Brahmin widow who was pregnant and contemplating suicide. She bore a son whom the Phules adopted and named Yashwant.

Savitribai respected Jyotirao not just as a husband but also as her teacher. He had given her a new lease of life, armed her with an education and helped her stand on her own feet. This is why in her letters to Jyotirao, she addresses him thus: “The Embodiment of Truth, My Lord Jyotirao, Savitribai salutes you!” The letters provide a glimpse into her belief in their mission to educate oppressed communities. In one letter, Savitribai responds to one of her brothers who admonished her for defying caste and religious norms: “The lack of learning is nothing but gross bestiality. It is the acquisition of knowledge that gives the Brahmins their superior status…my husband is a god-like man. He is beyond comparison in this world, nobody can equal him. He confronts the Brahmins and fights with them for teaching the untouchables because he believes that they are human beings like others and they should live as dignified humans. For this they must be educated. I also teach them for the same reason.”

More than Jyotirao, his wife deserves praise. No matter how much we praise her, it would not be enough. How can one describe her stature? She cooperated with her husband completely and along with him, faced all the trials and tribulations that came their way.”

While education was their main aim, the Phules also engaged with several other charitable efforts. A young Brahmin widow working as a cook in the house of Jyotirao Phule’s friend was raped by a neighborhood shastri. The widow, Kashibai, became pregnant and the shastri refused to take responsibility. When all efforts to abort the baby failed, she gave birth to a son. Afraid of the social stigma attached to conceiving outside of wedlock, she killed the baby. The police filed a case against Kashibai and she was later sentenced to life imprisonment in the Andaman Islands. Saddened by this, the Phules set up a home for the welfare of unwed mothers and their children. They advertised the facility by distributing rather provocatively worded pamphlets in Pune’s Brahmin colonies. This earned them the ire of a lot of Brahmins but also saved the lives of many pregnant widows at a time when upper-caste Hindu widows were not allowed to remarry and were shunned by society. Apart from this, the Phules had established a night school for peasants and workers a few years previously, which had also done surprisingly well; many workers from oppressed communities were admitted.

Savitribai was a revolutionary on par with her husband, spearheading many progressive movements in her individual capacity. She started the Mahila Seva Mandal, which worked for the awareness of women’s rights, and rigorously campaigned against the dehumanisation of widows and advocated widow remarriage. She also spoke against infanticide and opened a rehabilitation centre for illegitimate children. Savitribai also organised a successful barbers’ strike denouncing the inhumane practice of shaving widows’ heads. She also never shied from bringing her reformations to her own home: she opened the water tank in their house to the “untouchables”. This symbolic act challenged notions of purity and pollution inherent to the caste system.

When Jyotirao Phule passed away in November 1890, Yashwant objected to Jyotirao Phule’s cousin lighting his funeral pyre, arguing that this right belonged to the heir to Jyotirao Phule’s property. Accordingly, it was Savitribai who led Jyotirao Phule’s last journey, walking ahead of the procession. She lit the pyre, an act that invites censure even today. In nineteenth-century India, this was probably the first time a woman had performed death rites.

As an ode to Jyotirao’s exemplary life, Savitribai wrote his biography in verse, titled Bavan Kashi Subodh Ratnakar or The Ocean of Pure Gems. She also edited and published four of Jyotirao’s speeches on Indian history. Savitribai continued to carry forward the vision she had shared with Jyotirao. She took over the leadership of the Satyashodhak Samaj and was elected president.

Savitribai’s life reads like an endlessly inspiring storybook; the stuff of legend. She was the only woman leader of 19th-century India who understood the intersectionality of patriarchy and caste and fought hard against it. Known as Kaku (paternal aunt) by all her students, Savitribai was a loving but fiercely revolutionary soul who transformed many lives.

First published by Counter Currents