Written specially for the Vikalp Sangam

Himmatrao Kanjra Pawar stood in a patch of the grassland making different bird calls, starting with the female rain quail’s call. In no time we could see the male running towards him. “How many bird calls can you make?” we asked and his smile gave us the answer. Inumerable! “Oh,” he said calmly looking far away into the horizon towards the setting sun. “Kaustubh take out your binoculars.” We looked up in the direction that he was pointing and could see nothing, eyes blinded by the sun. “Yes ….yes…I think that is it!” said Kaustubh looking through his binoculars. A rush of excitement went through our veins. We were visiting Karanja Lad taluka of Washim district in Maharashtra to witness the much celebrated mating display of the male Lesser Florican. The florican inhabits a mosaic ecosystem of grasslands, agricultural farms and scrub forests. We had heard about the rare resighting of a female florican here in 1998 by the forest department with the help of the Phasepardhis. In the subsequent years we had also heard about the role this community and their traditional knowledge had played in protection and monitoring of this bird along with Kaustubh Pandharipande of Samvedana. We were here to understand this relationship between the lesser florican, the grasslands and the Phasepardhis.

Endangered Lesser Florican sighted in Vidarbha grasslands; photo Kaustubh Pandharipande

Foolishly staring at the sky, having seen nothing and not knowing where to look, we asked Himmatrao about the secret of his sharp bird spotting skills. “I have my tools,” he said, “just like you have your binoculars. I have my two eyes and my two ears…I can see for many kilometers and hear songs of birds across landscapes.” Himmatrao told us that he had seen many birds in his 63 years and his favourite is the Lesser Florican –kalchada for the phasepardhis. His greatest desire was to be able to see the Great Indian Bustard. “I saw my first kalchada when I was ten in 1972 and many since then. So when the forest officer came and asked me where he could see a Florican, it was not difficult for me to show him one.” He added with a sarcastic smile that the forest department had promised him a prize for showing the bird, which he never received. Soon after the visit of the forest department he was visited by Kaustubh Pandharipande, which has turned into a deep and long-term friendship. Himmantrao told us that he, his sons and members of the Phasepardhis community that they are in touch with, do not hunt the kalchada any more. Instead they have been monitoring their population along with Kaustubh.

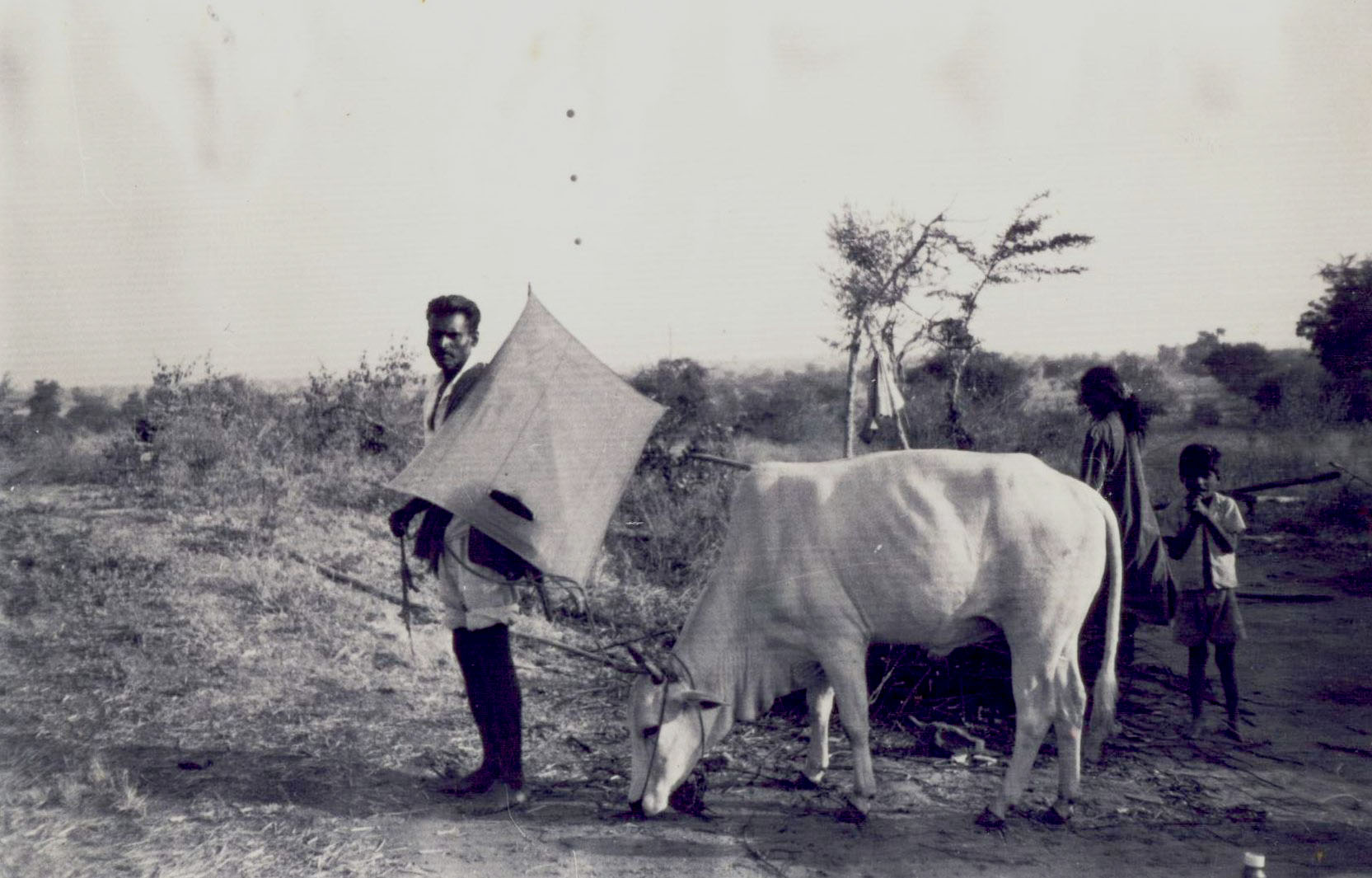

Phasepardhi tribesman with his trained cow which they use to hunt; photo Kaustubh Pandharipande

Kaustubh, a Nagpur based young and keen bird watcher and conservationist, visited this area in 1997, while working on a project to determine the status of the Lesser Florican in Vidarbha. While reviewing literature for the project, Kaustubh and his team had found British records mentioning the abundance of the Lesser Florican and the Great Indian Bustard in this area. Various British hunters in their monologues had also acknowledged the phasepardhis’ help in spotting the birds. Kaustubh decided to do the same and went to meet Himmatrao of Masa village in Akola. Through him, he was gradually introduced to other members of the community. These interactions led Kaustubh to realize that the declining population of the bird is not just a conservation issue but also a social, economic and political issue, all deeply interlinked with each other. It was then that Kaustubh started a not for profit organization-Samvedana and began working along with the phasepardhis towards conserving the Lesser Florican, regenerating the degraded grasslands, and ensuring livelihood options and dignity of life for the phasepardhis. Why did he start working on these issues?

Grasslands – an exploited ecosystem

Across India, grasslands are highly abused and under-appreciated ecosystems. Often considered as wasteland, these have been planted over by the forest department, allotted for non- grassland purposes such as urban expansion or industrial development, or brought under plough by powerful people. Similar fate has been of the dry land agriculture being practiced in these areas because of misjudged interventions. This mismanagement, exploitation and erosion of the grasslands and dry land agricultural practices have their roots in the colonial British policies of pre-Independent India. The black cotton soil of the Western Vidarbha region, where Washim is located, was important for the British for growing cotton for the Manchester cotton mills. Large swathes of pasture land were converted into cotton fields, which resulted in ruining livelihoods based on interdependence of dry land agriculture, livestock, and grasslands. This degradation has continued in post independence times as agriculture policies and practice support chemically intensive and mono-cropping based agriculture. Lack of meaningful assistance has meant that most farmers are not able to continue with traditional cropping practices which included diversity of crops such as traditional jowar, lentils such as toor (pigeon peas) and moong (green gram) and a variety of oil seeds. Under economic distress most farmers have sold their lands or have shifted to commercial crops such as Bt cotton and Soybean.

The Lesser Florican- a threatened grassland species

Habitat destruction – the grasslands and dry land agricultural fields – as described above has been among the major reasons for decline of grassland birds such as the Lesser Florican and the Great Indian Bustard. Extensive use of pesticides for commercial crops mentioned above has had serious impact on local flora and fauna including the birds whose diet consists of insects and grains. Additional threat is from unregulated hunting by communities (other than the phasepardhis) which do not follow any traditional taboos.

Phasepardhis – a socially, economically and politically marginalized people

Phasepardhis on the other hand have also had a long history of social discrimination and ostracism. Traditionally a nomadic hunting community, they were notified as a ‘criminal tribe’ under the Criminal Tribe’s Act 1872 by the British. After Independence, they were denotified in 1952, and their criminal status was repealed. Yet, as Kuldeep Rathod of Wadala village in Akola district says, “that hasn’t changed the public perception”.’ Additionally, the phasepardhis continued to be marginalized due to various reasons: hunting without license being banned after the 1972 Wildlife Protection Act of India; nomadic lifestyles not recognized as a means of livelihood in government policies and practice; lack of accumulated wealth owing to their traditional lifestyles; and having no access to or ownership rights over land and surrounding forests and grasslands. Socially discriminated against and officially criminalized, illegally pursuing the only means of living that they knew i.e. hunting, the phasepardhis spent much of their time escaping forest department or the police. People relate many stories of phasepardhis from this area who have been picked up by the police and are still languishing in jails without any evidence. “Our work with Samvedana began with the need to change the narrative around us and to gain social dignity,” said Kuldeep sitting close to his chicken-rearing shed. “There have been so many misconceptions about us and our hunting practices. Being traditional hunters is not equivalent to being criminals! What people don’t know is that unlike hunting in general, we have an elaborate system of rules and taboos to be followed while hunting.” The phasepardhis in this area still use traditional methods of hunting e.g. their traditional hunting gear – a trap made of bamboo and horse hair (khandari), and follow traditional hunting taboos like not hunting females and the chicks in the breeding and rearing season. “Very importantly, not everyone can be a hunter; you need very sharp mental faculty, sharp eyes, sharp ears, and quick decision making skills. We chose our traditional leaders based on these skills. Good hunters often made good leaders as they would stay away from intoxicants and unethical activities. Only the ones who are quick at spotting the birds and who follow the rules will be accepted as hunters within the community,” adds Himmatrao with pride written on his face.

Co-generation of knowledge towards a holistic transformation

Over the years, as Kaustubh began to understand the phasepardhis and his friendship with some of them deepened, he could see the underlying but significant connections between the Florican habitat and population recovery and the struggle for a dignified life of the phasepardhis. With help from Himmatrao, Kaustubh slowly connected with more and more phasepardhis, mainly youth and began a journey towards co-generation of knowledge. The work began in 2001, and till 2005 Kaustubh and the phasepardhis youth undertook a number of exploratory studies.

The first of these was towards preparing a People’s Biodiversity Register (PBR). This included field surveys of birds, their populations and habitats, documenting the local knowledge and practices around them, monitoring and protection of the birds. Kaustubh ensured that regular formal and informal discussions among the youth, often based on the findings of the study, remained an important part of the methodology throughout the project. The project provided a small honorarium for some of these youth, which helped facilitate these discussions.

Discussions on Phasepardhis and hunting for livelihood

The first of these discussions was on phasepardhis’ relationship with the main species of birds that they hunted, their population dynamics at the time of discussion, in the past and likely future scenario. This was an important discussion for the youth to understand a complex socio-economic situation that they faced and which was likely to get worse in times to come. Over a period of time this discussion helped the youth understand and articulate their own local traditions and knowledge systems, including traditional systems of monitoring bird populations. What also emerged in these discussions was that the populations of these birds were indeed dwindling. Phasepardhis identified a number of reasons for this, including habitat destruction; extensive use of pesticides and herbicides; and sport hunting by non phasepardhis who didn’t follow hunting taboos.

Tandapanchayat meeting in Wadala; photo Sahebrao Rathod

This led to the next discussion on what was the future scenario for these birds and for the livelihoods of phasepardhis, who extensively depended on hunting for survival. Clearly the current rate of decline in bird population would not be able to support the livelihood for the next generation of hunters. At the same time given the external factors, ensuring a healthy population of birds was not entirely in their hands. The youth began to discuss and explore possibilities of diversifying livelihoods for themselves and for the future generations.

Discussions towards exploring reasons for economic weakness, internal inequities and social discrimination against phasepardhis

The second discussion based exploration to understand reasons for social discrimination against the phasepardhis as also the weaknesses within the community such as economic disprivilege, internal inequities (particularly gender) and weak leadership. In the initial discussions, the youth identified “not having leaders from their community associated with political parties” as reason for their weak economic and social status. This led to a long discussion on whether politicians really work for people’s benefit. This discussion helped in identifying, “effective and good leadership (not necessarily political leadership) within the community” as an important need. The older people described that selecting leaders was traditionally an important process and community leaders were selected based on some qualities, including:

- Being just and fair

- Being wise

- Being incorruptible

- Being generous

- Working for the benefit of others and not for self interest

The youth began to discuss whether these qualities were being fulfilled by their existing community leaders. The phasepardhis have a traditional jati panchayat , which largely works on conflict resolution. Jati panchayats rarely discussed issues of governance, natural resources, employment, or social discrimination. Even in their limited role there was no involvement of women and youth. Additionally, over the years the positions of leadership had become hereditary, and leaders often lacked leadership qualities, were often drunk, corrupt and easily influenced. Youth felt the need for a new institutional structure which could address these issues and be inclusive of women and youth. Women particularly face serious discrimination with many oppressive social practices, leading to social injustice including within jati panchayat decisions and exclusion from any decision making processes.

Wadala youth and kids preparing herbarium for grass identification; photo Kuldip Rathod

Beginning of transformation

The knowledge thus generated and discussions around them have in the last decade or so have led to four important ongoing processes;

- Community monitoring, mapping and protection of the lesser florican and its habitat

- Community-based grassland restoration programme

- Collective self action towards improving the social and economic status of the phasepardhis.

- Self- empowerment, internal reworking and strengthening traditional decision-making institutions (including by engendering them).

Community monitoring and protection of the lesser florican

Considering the severely declining population of the grassland birds and their fast dwindling habitat, of the 13 villages in this area where the phasepardhis live, the effort of the phasepardhis youth has been to monitor, protect and map the florican population. Anyone sighting a florican informs their network and Kaustubh. These elusive birds are usually sighted at the time of the mating display of the male, which continues at the same site till he finds a mate and he often returns to the same site year after year. These sites are then mapped, monitored regularly and protected by the community members. “Considering that 60% of the florican habitat is private farmlands (owned by non phasepardhis) it becomes difficult to ensure long-term security for this land but an effort is being made to protect the population, sometimes by keeping the site secret and sometimes by negotiating with the farm owners,” says Kaustubh. Amongst the phasepardhi villages, few like Wadala have taken an oath or Palti to gradually stop hunting of threatened birds completely.

Community grassland restoration initiative

Of the 13 villages, Kanshiwani, Parabhavani, Pimpalgaon and Wadala have started regenerating and restoring their grasslands and forest lands. In Wadala village (which we could visit), 28 families decided to protect and regenerate 100 hectares of surrounding forestland (a combination of grassland and thorny forest). This initiative was subsequently supported by the forest department under their Joint Forest Management (JFM) scheme. “It was possibly the first time in Maharashtra that a mutually respectful collaboration between the forest department and phasepardhis was initiated,” says Kaustubh. This restoration initiative resulted in increased grass cover, reduced soil degradation, increased availability of firewood, wild fruits, medicinal plants and significant increase in the availability of diverse and endemic species of fodder. “The Wadala grassland is currently protecting over 47 different varieties of grass, including pawnya, marvel, kunda and harala grasses, which are now rare elsewhere but are important for many grassland birds including the Floricans,” says Kuldeep.

In recent years, Pani Foundation has also helped carry out soil and moisture conservation and construction of check dams. Village children, with help from adults, have started a nursery of around 20,000 plants of different wild fruits, endemic fodder species, and local medicinal plants. “We read in the newspapers that 13 crores have been spent in Akole district for plantation activities by the forest department. We are doing this all on shramdaan (voluntarily) without any financial support and our plantation is more diverse, of local species and more successful,” says Kuldeep, as he walks us through the regenerating grassland. ‘Of the 273 ha of forest area in our village, we are completely protecting 100 ha, the rest is being used in a self regulated manner to meet our subsistence needs.’ The village has a number of rules and regulations for protection of this forest such as, employing a common herder who would take the livestock of the entire village and ensure that they don’t stray into the protected zone, fines for violations, preventing outsiders from stealing resources –which has sometimes led to conflicts and police cases.

Youth group from Wadala village with their fodder harvest from conserved area PC- Kuldip Rathod

“We don’t have any legal rights over these forests which makes our future unsure and protection now difficult. We will be filing a claim under the Forest Rights Act of 2006 soon,” adds Kuldeep.

Towards socio-economic change

“Considering the various constraints involved in hunting as a profession including the stigma and a constant threat of being caught by the forest department, very few phasepardhis want to pursue hunting as a livelihood or would want their children to do so,” says Smita (name changed) who we met in the grassland. While some have taken to nomadic trade, selling cheap plastic wares at village markets, others have moved to wage labour, particularly for picking cotton, livestock rearing and farming. For example, Wadala which is a 100% phasepardhi village has 28 families of which 19 are small land owners (less than 5 acres of land) and 23 go for nomadic trade (seasonal) or wage labour. The land owning families said farming is the least lucrative of all employment opportunities. Farmers often don’t even recover the cost of labour that they have to employ. Wage labour and nomadic trade bring in a good income, but not everyone has the skills for that. Consequently, a number of steps were taken by Samvedana and the youth based on the outcomes of the youth group discussions to diversify livelihoods, particularly for women and youth. Around 18 self-help groups (SHG) were formed that provided financial support to various livelihood generating activities such as sustainable goat and chicken rearing, dairy and fodder regeneration, among others. The SHGs collectively managed to create a corpus of nearly Rs.400,000 and different members have availed and returned loans worth Rs.700,000 over the years.

In villages like Wadala, the income now is also from the sale of grass and milk from agriculture and livestock because of availability of fodder and water in the regenerated grassland. The 28 families which regenerated the above mentioned grassland now collectively make an additional income of Rs. 200,000 per year.

Towards Socio-political change

As the youth realized through the discussions, social change cannot be brought about without impacting the decision-making institutions. Phasepardhis didn’t have a traditional village assembly or a gram sabha, and jati panchayats as mentioned above were increasingly corrupt and dysfunctional. The youth from the 13 villages including Wadala, decided to constitute tanda panchayat (of these 3-4 are functioning well while others are in the process of self-strengthening), which was inclusive of women and youth. The tanda panchayats were linked to the Panchayats under the Panchayati Raj System. While the jati panchayat was at the level of the community, tanda panchayats were instituted at the level of each hamlet, which included all adult members of the hamlet and provided an opportunity for all to participate in the decision making process. Each tanda panchayat elects an 11 member executive committee of which 50% are women. These members can be changed anytime if the village is dissatisfied with their actions. The rules of the tanda panchayat are a mix of non-discriminatory traditional ones and modern democratic values. For example, the old practice of oral rules continues but compulsory participation of women and youth is a new practice. ‘We follow consensus-based decision making but we do slip once in a while and take the decisions that the majority wants,’ says Kuldeep, while narrating the evolution of the tanda panchayat.

School and tribe kids during environmental education workshop learning grass production mapping; photo Sahebrao Rathod

The Youth Group Networking

In 2000, the youth also decided to form yuvak gats (youth groups). Four villages namely Titwa, Masa, Wadala, Kanadi have formed yuvak gats in their villages. These yuvak gats have played an important role in the studies, discussions and all the activities mentioned above. Their work has slowly expanded towards understanding and documenting cultural practices, songs and stories. They have been playing a critical role in empowering the tanda panchayats by taking up other social issues such as domestic violence, caste issues, youth leadership, amongst others. The yuvak gats are constituted of all youth members, including women. The attempt of the yuvak gats have been to connect with the youth from all the 68 phasepardhi villages in Vidharba region and work towards mutual learning and empowerment.

Recognition of their effort

In 2012, an attempt was made by the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) and Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) to prepare a State Action Plan for Bustards’ Recovery Programme that accepted Kaustubh’s argument to include the phasepardhi’s traditional knowledge in Bustard conservation model. In 2014, a draft plan was submitted to the forest department for the conservation of the bird. The plan was prepared by the phasepardhi s with the help of Samvedana. It was possibly the first time that the government formally recognized the traditional knowledge of the phasepardhis enough to entrust them to draft a conservation plan.

Exposure visit of forest department staff during regional workshop at the Wadala’s community conserved grassland; photo Sahebrao Rathod

India Biodiversity award prize

At the 2012 Convention on Biological Diversity COP in Hyderabad, the efforts taken up by Wadala village were recognized and they won the prize of 1st runner up in the category of Community Stewardship. Representatives from Wadala were felicitated by the then environment minister.

Process of change however is a long and continuous process and the phasepardhis, the floricans and the grasslands still have a long way to go.. ‘Can buildings feed us, sustain us? I wonder!’ said Himmatrao when we asked him how he sees the future of grasslands and florican conservation. The lesser florican population is still critically endangered, the grasslands are continuously falling victim to rapacious wants of real estate and industries, and the intensive mono-cropping patterns that threaten the florican’s population are backed by government policies. The little glimmer of hope in all of this is the continued efforts of the phasepardhis working towards reviving ravaged ecosystem through social, economic and political transformation. We do hope they are successful in getting custodianship rights or Community Forest Resource Rights under the Forest Rights Act over the forests that they are protecting to ensure the long-term survival for themselves and for the lesser florican.

The authors are with Kalpavirksh

Contact the authors

A shorter version of this article was published by Mongabay

Read a translation of this article in Marathi – फासेपारधी आणि तणमोर