Written specially for Vikalp Sangam and ‘People in Conservation’ NEWSLETTER

Abstract

Started in 1977, Tharangini studio is the oldest and last surviving hand block print studio in Bangalore. Much thought is given to concerns of environmental sustainability and therefore natural dyes are predominantly used during the block printing process. The organisation also gives importance to matters related to recycling, waste management and fair-trade practices at work. Apart from this, they conduct free outreach programs, particularly with specially-abled artisans at various Autism centres across the city. Tharangini’s mission therefore, is not only to uplift artisanal communities throughout the country, but also to provide vocational training to underprivileged groups. The organisation’s extended family of artisans include: hand block printers, wood carvers, fabric dyers, embroidery artisans, colour mixing and fabric finishing experts.

Introduction

Tharangini is a block printing studio based in Bangalore. It has one of the largest collections of wooden blocks and some of the finest block print artisans. It was established in 1977 by Lakshmi Srivathsa and is now run and managed by her daughter Padmini Govind. Right from its inception, Tharangini was a place which valued and followed ethical labour practices, was passionate about uplifting artisanal communities and used eco-friendly dyes. Their commitment to the above still continues and today they are also a fair-trade certified organization.

History

In the first 30 years of their existence, Tharangini was primarily designing sarees along with the printing of some fabric, made into garments. They worked mostly with silk since the state of Karnataka is the largest producer of silk in the country. Also back then, everybody wore silk, even Lakshmi herself. Their mode of operation was entirely business to business (B2B). Some of their clients included airlines like Air India and Royal Nepal who would buy beautiful hand block printed sarees from Tharangini, to be worn by their air hostesses.

However, in 2007, when Lakshmi handed over the reins of Tharangini to her daughter Padmini, changing times called for a change in their business strategy as well. As the silk and sareemarket was barely able to hold the fort, Tharangini switched to fabrics for home furnishings in 2007 which continue to be exported till this day. Their mode of operation continues to run on B2B and the fabrics are exported to other businesses that make garments at their end. Locally, they have also tied up with a garment brand and a fair-trade certified garment unit based in Bangalore and this helps connecting Tharangini with other members of the community. “It’s about bringing in community. It’s not about profit margins”, said Padmini. Another reason that Padmini gave for Tharangini to move into export was to be able to afford fair-trade wage standards for their artisans.

Structure and Governance

Tharangini is a sole proprietorship in the name of Padmini Govind’s father. However, Padmini says that there are no titles in Tharangini and only roles that individuals fulfil. “I don’t want to go and call myself the director. It doesn’t belong in an artisan business at all”, she says, “That’s the way we’ve been structured since 77”. Tharangini does not believe in the idea of titles, where people cannot engage in activities beyond their job position and description.

The kutteeram or workshop hut at Tharangini, photo: Sneha Gutgutia

But certain roles are defined, for instance they do have personnel for matters related to administration and accounts. Overall it’s a small team consisting of around five block printers, two colour mixers, one block maker, two in admin and Padmini herself. However, the ethos of Tharangini is such that each helps the other out as and when required. For instance, Padmini will engage in the process of mixing colours, making tea for all the members and will also assist the admin – Mary – with computer based work, since she is not too tech savvy. Sathish, a young artisan who is adept with computers also helps Mary as and when he can. Krishnappa, who is an experienced block printer, helps Bhanuamma and Yashodhara who are the main colour mixers and also handles all the post processing of the fabric which includes– rolling, steaming, curing, and washing. “We’re very small and there is not one size that fits all; to say that this is the way it has to happen”, says Padmini. The structure of Tharangini as an organization thus works on mutual understanding and cooperation.

So does the governance. “We run like a little village panchayat”, says Padmini. Once a week or once in ten days, they have a round table where members discuss any issues faced – whether it is about something that was said or done, or something which does not feel right and so on. She says it is because they have such a strong team, for instance like Krishnappa, Govindanna and Bhanuamma who have been here for three decades, which makes it easier to discuss and eventually resolve issues. In the case of an issue which cannot resolve, the team tries to understand what they can do differently about it. Everyone will provide suggestions. Padmini believes that the senior team members have been at this a lot longer than her, and therefore she takes their feedback into consideration. And they too seek her suggestions because they realise they are in this together. She says, “It’s a constant push to make Tharangini run and we all have to be a part of this constant push.”

Environmental Sustainability

What distinguishes Tharangini most from other craft centres is probably the effort they take to ensure environmental sustainability and the sustainability of the craft itself. Tharangini being a printing studio benefits from not having the use for tons of water, electricity or generating fabric wastes such as leftover bits of cloth from cutting and sewing, which happens in most garment factories. They use Ready for Printing/Dyeing (RDF) fabric that is made available to them from the businesses that place orders with them. In most cases these are printed and returned to the businesses that then do dry heat treatment of the fabric to fuse the colours with the fabric.

Tharangini also uses natural yarns not only for printing but also for the padding used in colour trays during block printing, which is cotton gauze cloth and mulmul. These cloth pieces are washed and reused until they practically disintegrate. The dyes they use are mostly organic which are also carefully mixed in quantities that each order demands. Any leftover dyes are sent to be used at autism centres, an aspect which is discussed towards the end of this case study. For any steam treatment they have to do on their printed fabric, Tharangini uses Liquid Petroleum Gas for fuel and newspapers for insulation. The newspaper is returned to the same vendor from whom it was bought for recycling. The effluents generated due to washing block prints, gum-arabic from fabric when discharge dye printing[1]has been done, and natural dye from sarees, are safe as the materials used are natural or certified as safe to use. However, as an added precaution the effluents are still treated in an effluent treatment plant. The plant was installed in the year 2000 and the water it discharges is potable. The pro-activeness that is seen in Tharangini towards sustainability of the environment is commendable and desirable in many other garment and dyeing factories across the country that generate lots of waste or are heavily dependent on water and electricity. However, whether this model can be replicated in such times is a question one has to consider.

Dye making

The process of dye making that Tharangini follows is a long and intense. It is much longer for the preparation of natural dyes than for synthetic ones. The extraction of colour from the raw materials for natural dyes involves drying them in sunlight, and once dried, it is followed by boiling them in water while simultaneously pressing them using a pestle and finally letting the concoction cool overnight. If a deeper shade of the colour is required, the entire process is repeated and the dye is collected in a separate container. Moreover for the dye to hold, the cloth is first dipped in Myrobalan[2]extract, then dried and this process is repeated all over again to give the cloth an off-white shade that provides “character” to the colour and binds it well to the cloth.

This process of preparation of natural dyes can take anywhere between one week and two to three months depending on the colour and the shade. For example, the black dye made by fermenting a mixture of iron liquor[3] and palm jaggery[4] takes almost two months to make. The duration of fermentation can be increased or decreased depending solely on the shade of black that is desired. Though once prepared and extracted, this organic dye has a shelf life of six to seven months and thus, it can be prepared in large batches that then lasts for months.

Given below is a list of some of the raw materials used for preparation of natural dyes.

| Raw material source | Colour of dye extracted |

|

| Achiote seed | Orange | |

| Alkanet root | Purple | |

| Gum Arabic resin | Off white (mordant) | |

| Indian Madder | Red | |

| Myrobalan | Off white (mordant) | |

| Pomegranate | Lime green | |

| Turmeric | Yellow |

On being asked whether they prepare all organic dyes from scratch at Tharangini, Padmini said that they also procured extracts available in powdered form from companies in different parts of India- Hyderabad, Kolhapur, Jaipur and Dindigul- that are easier to use than making the dye from scratch. “So you get the powdered version. It’s like buying vanilla essence versus starting with vanilla bean for cooking”, she explained. She also referred to the inconsistency in the shade of the colour used for block printing when they are prepared using naturally dyes. Sometimes they get a nice shade with their dyes but sometimes the colours doesn’t really come out well, so they prefer using the powdered extract for making dyes in case of some projects.

Padmini also shared with us some information about the other kinds of dyes they use at Tharangini. Besides the organically prepared ones they also use synthetic dyes that are Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) certified. The GOTS mandates that the organic status of any textile be ensured: right from harvesting of raw materials involved in cloth making and dyeing, by following manufacturing processes that are environmentally responsible, to proper labelling of the product in order to provide assurance about its organic status. “I would love to use things that are only organic but I do know that from the production point of view, I have to be practical. So, I don’t have any dilemma using something that is GOTS certified,” said Padmini when asked if she faced a dilemma while using GOTS certified synthetic dyes over organic ones. “It depends on what the customer wants,” she added.

After preparation of the dye, mixing and achieving the shade as desired by the client becomes a challenging task. Tharangini currently has only one experienced colour mixer – Bhanuamma, who has been working here for over thirty four years now, besides Yashodhara, a young apprentice. She recalls that the first dyes she prepared at Tharangini were red using Indian madder[5], brown by mixing extracts from Indian madder and black Myrobalan and black using iron liquor & palm jaggery. She mixes the colours in a bucket using her hands, then immerses a small swatch[6] of cloth in it to approximate what the colour would look like when being printed on the finished fabric.

Bhanuamma in the process of colour mixing, photo: courtesy Tharangini website

The various raw materials used to create dyes, photo: Anmol Chowdhury

Bhanuamma is proud that she works with eco-friendly materials that minimize sustainability problems and safeguard health. When asked about the rate of procurement of raw materials for preparation of natural dyes, she said that it has been slow due to a general decline in forested areas where these raw materials are found.

Block making

A crucial aspect of the dyeing process at Tharangini is the making of wooden blocks used for printing designs on fabric. The wood carver at Tharangini – C.H. Sreeram- is apparently the only wood block maker in the whole of Karnataka. However, wood carving is not a traditional occupation for Sreeram. In fact he comes from a family of farmers and learnt wood carving only out of pure interest and fascination when he moved to Bangalore about thirty-five years ago.

The wood for making blocks at Tharangini is sourced from vendor Timber Layout (Mysore Road), where there are usually two types of teak woods – Burma Teak and Ghana Teak. Burma Teak is what Tharangini uses because it is solid good quality wood, but is expensive and costs INR 8000 for a 1 ft by 1 ft piece. Ghana Teak on the other hand is sold for Rupees 5000 but has the tendency to bend. Local wood is not of adequate quality it comes in smaller pieces and sometimes has holes in it…

Newly purchased wood is levelled and titanium white[1] is applied onto the piece of wood. After it dries, the block maker traces the design on the teak wood by marking the outline. With a set of hand tools, some of which curve and others are angular, the block maker keeps chipping off the wood until the final block is ready. The time taken for creating a block depends on the level of intricacy of the design. While a simple design might take between half a day and a day to create, an intricate design can take up to four days. Tharangini employs Sreeram to make blocks and he comes twice a week to their campus to understand the designs required for new orders. Today Sreeram does all the tracing on the wood, while he delegates the tasks of carving to other craftsmen he has employed for the purpose.

For Sreeram, Tharangini is his primary client that he receives most of his orders from. Design students also place smaller orders with him. Sreeram says that there is a general preference for traditional designs amongst the clientele. There are many challenges that this craft of wooden block making is facing. With the introduction of screen prints, the overall value of block print has come down since screen printing is a faster way of producing larger quantities. Younger people also find sitting for long hours, which is usually the case while making wooden blocks, taxing. The compensation is hardly adequate. However, Sreeram is able to sustain his craft owing to the mix of orders he gets from Tharangini and the orders he receives from individual clients.

The process of wood carving and some wooden blocks on display at Tharangini, photos: Sneha Gutgutia

(Titanium White is the more common of the whites used for painting. It’s known for being bright white, almost bluish, and has excellent opacity)

Block printing and printers

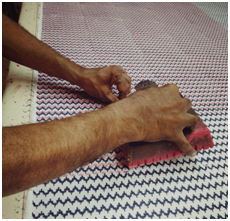

Block printing at Tharangini predominantly uses wooden blocks, carved with designs on them, to make an impression on the cloth. This is done by first dipping the block in the dye and then carefully placing it on the cloth. The procedure requires the cloth to be washed free of starch so that the colours can stick on them. The cloth is then stretched on a flat surface and fixed on it with pins. The dye that has been prepared is kept in a tray, beside the printing table, and contains glue and pigment binder. The block is not directly dipped in dye but pressed against a layer of wash cloth soaked with this dye so that the block does not pick any extra colour. The teakwood blocks, once prepared, are also dipped in oil for a few days before being used. After printing has been done on the cloth, the block print is first allowed to dry, and then the cloth is covered in newspaper and is steamed. Only when the discharge printing is done, the cloth is washed to rinse off any resin (gum Arabic) that is sticking to it, dried again and finally ironed before it is ready. At Tharangini, skilled bock printers combine multiple overlapping blocks to arrive at complicated designs.

Tharangini has five skilled block printers producing some very exquisite designs on cloth. The youngest of them is Sathish who has been with Tharangini for ten years now and the eldest are Krishnappa Bhat and Mallikarjun who have been with Tharangini for forty-two years and forty-five years respectively. The names of the other block printers are Shankar and Govind Raju, who have also been with Tharangini for ten years and thirty years respectively. Interestingly, most of them are the first in their families to take up block printing. Sathish and Mallikarjun come from a family of farmers, while Krishnappa’s father worked as a bank employee and ancestors were farmers. They all took up this profession of block printing out of sheer interest and have made it this far because of their skill and talent. Years ago, Krishnappa had left his job at Tharangini for five years during which he tried his hands at a small business of a paper and milk agency. But he soon gave that up and rejoined Tharangini. Though they all have had minimal formal education, their block-printing work they say, is the one which requires and demands precision and focus for long hours. Even a small mistake can lead to rejection of an entire fabric that has been printed on. The blocks too need to be handled with care so that it does not wear off or fall and break. They said it can sometimes take up to three hours to print an entire stretch of fabric, and this is dependent on whether it is a single block print or if it is multiple colours using multiple blocks.

All the block printers seemed satisfied and happy about their work at Tharangini. But they all have different reasons to be at Tharangini. For Sathish it is the awareness of the fact that Tharangini exports quality products to foreign countries, that there will always be a market for clothes and because his primary interest is in delivering good quality products. For others, such as the more experienced printers, it is the familiarity of Tharangini and the work that has kept them in this profession and ecosystem year after year. Apart from this, they all also seemed satisfied about their salaries and that it is fair wages. They don’t work on Sundays and on government holidays. Additionally, they get twelve days of paid sick leave and also get paid for overtime. The work environment is healthy with mistakes not being pinned on individuals and issues being discussed every ten to fifteen days with all members. There are also tea breaks which give much relief to the artisans who have been working with full concentration standing at one place for hours. It also allows everyone to come out into the open space and have some chit-chat.

The process of block printing on fabric, photos: Sneha Gutgutia

The artisans take little interest in technology, except Sathish, and have little knowledge of what happens to the fabrics after they have been printed or who buys them or who is the end user. This is despite the fact that these details are shared with them from time to time and artisans interact with designers and interns coming from across the globe. None of their children or families has taken up block printing after them. “The attires that we wear are not fancy and the dyes we use to print, they (youngsters) feel are harmful. Most of the day we are in these clothes (spoiled due to dyes) working with dyes, this is not a sight that would appeal to a youngster”, says Mallikarjun ruefully. Shankar says, “There is nothing beyond in this work… Children now gauge what are the perks and benefits of working”. Sathish and Govind Raju agreed that the salary is also not enough to bring youngsters into this line of work. “Whoever is still doing this kind of work are older people like us”, remarked Krishnappa. Both Krishnappa and Mallikarjun don’t complain about this and have left their children to decide what they want to do in life. Only Sathish is keen to pass it onto the next generation, by insisting that he will teach this skill to his daughter as he believes that no knowledge should go waste.

Hand block printing is dying not just because the younger generation is not keen in learning the craft but also because of the introduction of screen prints. However, Krishnappa says that in screen prints, there is less freedom to manipulate the designs as the patterns are fixed. Plus, there is scope of very less creativity. In comparison, in hand printing, one can create ten different designs using the same block. Such textiles, they said, were in high demand until thirty or forty years ago, but since then there has been a steady decline forcing many artisans to take up alternative careers or additional work on the side. In fact, such artists are scarce to find now. Though they had little knowledge about how many block printers were left in the city, traditionally it used to be the Jangama community who practiced block printing. But there are very few who follow the tradition now. Under such circumstances, the importance of a space like Tharangini becomes of prime importance in sustaining a dying craft and artisanal livelihoods.

Fair-trade practices

An aspect which sets apart Tharangini is the practice of fair-trade. Fair-trade in institutional terms implies better working conditions, fairer deal for exporters like Tharangini, improved social and environmental standards, no child labour, freedom for workers to express themselves and so forth. For Tharangini, Padmini says, “It [fair-trade] really means to do justice to my team, financially. They should benefit from the success of Tharangini. That’s the bottom line of fair-trade.” There are multiple fair-trade bodies and the one that Tharangini is closely aligned with is NEST, based in New York. NEST does ethical certification for artisanal-clusters worldwide. What Padmini likes about their process is that they are artisan focused. Artisan businesses don’t run like regular businesses, so when someone like NEST do ethical compliances evaluations it is focussed on to how the artisanal business is run. This she compares with big World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) bodies which analyse businesses in general. Tharangini signed up with NEST way back and Padmini says they were enlightened by them on a number of things which they had earlier taken for granted. For instance if they are outsourcing work to women who are working out of their house, how do they manage their wage conditions there? Similarly, she says, while they maintain proper wage records as well as advance records, they also need to ask themselves– “Are we harassing them to get the money back? Are we making them work more hours than they feel like? Are we giving them sick leave benefits? We should not in any way be exploiting them”, she says.

Apart from keeping proper records and ensuring healthy working conditions, a crucial fair-trade practice followed by Tharangini, on their own accord, is that of profit sharing. Once a year during Dussera, the team calculates all the profits made during that year. And then depending on the seniority within the organisation, it is divided. She also adds that “…see there is the ecosystem of Tharangini that you see and then there is the ecosystem you don’t see in Tharangini, and that is equally important.” As an example of the latter, she was referring to Usman Bhai – who is the Saree polish person, or to those who do embroidery for them. There is a cosmos and ecosystem outside of Tharangini and profit sharing with those like Usman Bhai is how they show their appreciation to them. At the same time she believes that being fair applies to Tharangini’s clients as well; one cannot go charging the moon to be fair to the artisans. Therefore, in the practice of being fair, it becomes crucial to find that balance between the people supporting the vision and the producers behind it.

Outreach

One of Tharangini’s missions is to provide vocational training to underprivileged groups, which they carry out through their outreach programmes. Through this, Tharangini engages with autism centres in Bangalore where they teach adolescent children or young persons enrolled in these centres the techniques of block printing. The goal is to develop an income-generating skill. Padmini feels that the outreach programme really helps them to achieve their objective of sustainability as well, which at Tharangini means numerous things, but most importantly implies sustaining the handicraft itself. At present, Tharangini engages with four to five centres for the young autistics in Bangalore. However, many more collaborations are in the pipeline as other centres are learning about the success Tharangini has had with autistic persons at these centres.

Tharangini, since the time of Lakshmi, had always been keen on outreach. During Lakhsmi’s time Tharangini would do free workshops for Karnataka Women’s Welfare Board, teaching women about natural dyes among other things. “She always had that giving or sharing personality”, says Padmini and it inspires her. Padmini too organized workshops with the Association of Physically Disabled and the Spastic Society. But it all changed one fine day when Jayshree Ramesh, who is the founder for Asha foundation for Autism, asked Padmini to organise a day-long workshop for adolescent autistic children from four different centres. They never thought it could be a serious vocational training for these children, but the children seemed to just love the colours. Teachers at a centre, NavPrabhuti Trust (http://www.navprabhuti.org/), who were also mothers of the children in the centre said that their kids would do block printing for seven hours straight. It was almost therapeutic for them.

They realized that this could be an avenue for engaging young autistic children at these centres in some income generation in future. Besides, working with autistic children is different. They like to stick to a routine and don’t like a change of environment. So, it was also great to have found something they could do in future for a living while enjoying the activity, in their own setting. However, it is only recently that the children have gained the skill level needed to do block printing of intricate designs. “In a centre of 20”, says Padmini, “Only four would have gotten to that level of skill”. However, the process engages many more children of the centre who do side jobs like aligning the paper to be lined with bags, pressing the block hard once it has been placed on the fabric and sticking things. Although these children are also given a small share of the profit that is generated by selling of the products made, the idea is to help develop skill sets that can be useful in future. The silk stoles and pouches they make are being showcased and sold at a small scale at Tharangini itself. The response from customers has been very good though Padmini thinks it is still not time to open the floodgates and to give these children a large number of stoles to print. They are thus at a very nascent level with respect to marketing. “It’s growing organically”, says Padmini. At Tharangini, they are happy with the way they have been able to engage these children so far and to generate whatever little income they could out of it.

However, keeping in line with the quintessential spirit of Tharangini, the entire team at Tharangini is also a part of and a driving force behind the outreach programmes. Sathish and Krishnappa keep visiting these centres to teach the children the various methods and techniques involved. Bhanuamma and Yashodhara, who are the colour mixers, take extra care to ensure the shades that are being given to them for printing are right. The family of artisans and staff at Tharangini are proud of the fact that they are involved in such outreach programs. They are definitely behind Padmini. It needs to be accepted like a shared objective for it to work, explained Padmini with a smile.

Block printing on stoles of jacquard fabric done by autistic children as part of Tharangini’s outreach programme, photo: Sneha Gutgutia

Reflections

Sustainability is at the heart of Tharangini. It has been sustaining the craft of hand block printing in the context of Bangalore, which does not have an ecosystem that supports crafts like one would find in Jaipur or Kolkata. In the last decade, a lot of the printing units have shut down in Bangalore. “Either they have converted into screen, or they are just gone…or owners have decided to move to digital format”, explained Padmini. This leaves artisans to move out of this field into other fields to earn a livelihood. Considering the current state of this field, Tharangini has indeed set an example by keeping the studio and the livelihoods of the artisans alive and intact. They have also, from the very beginning, recognised the importance of ensuring environmental sustainability of their enterprise. The dyes used are mostly natural or organic certified, water is recycled and other raw materials namely, paper and fuel is used responsibly. The studio also has the largest collection of hand blocks in India. Apart from the above, Tharangini also promotes fair-trade and fair wage standards for their artisans and values them and their skill as something beyond a mere commodity.

An important aspect to delve into is the scale and cost of production at Tharangini in comparison to that followed by majority of producers. Today there are a lot of small enterprises similar to Tharangini, operating on similar lines of natural dyes, promoting the art and so on. However, with the costs of raw material, labour and land increasing day by day, such sustainable products are typically a lot more expensive than mass-produced goods. How do such enterprises expect their wares to be affordable and accessible to the general populace? And can such a model be replicated across large scale garment factories? The scope of such line of thinking itself is limiting because Tharangini and the likes need to be looked at as producing for a niche market amidst the whole scale of producers.

Though we see an increase in the demand for these niche and sustainable products, how willing is the future generation to take this up as a career? Some of the older artisans themselves feel that there is not much scope for the next generation in this field. How will such a setup sustain in the long run? Though the artisans were happy about their work at Tharangini, they did not place as much importance to the fair wages and distribution of profits they received as much as the emphasis that is given to it in fair-trade by the world outside. Might altering the structure of Tharangini from a proprietorship into a collective of artisans, such as a cooperative society, change this scenario? Will more responsibility bring more sense of ownership in the work and in turn more interest among the artisans? “I think it’s a great thing if it can be well-run”, remarked Padmini. However, she also pointed out that not want to engage in the hassle of managing. “They just want to come and stay engrossed in their work”, she explained. This despite the fact that such a collective and association could bring in more tangible benefits to the artisans.

The trouble with such enterprises is that they are exoticized. And maybe such exoticizing works for the enterprise to bring in more customers and orders. However, one also needs to look at the work carried out by the artisans as work/employment which pays the house hold bills. This is a fine balance that Tharangini must maintain – for the art and craft as well as for the individuals creating them.

Padmini envisions a multitude of things for the ecosystem which is Tharangini; from thoughts on collectivization within the artist community, to promotion and benefits from the state, to understanding what artists at Tharangini do in their everyday life, to having an all-women run centre, her vision encompasses ideas and realities that need both exploration and reflection.

[1] Discharge dye printing is a method of printing where a design is made on a dyed piece of cloth by applying a substance that bleaches the cloth hence leaving a pattern on it.

[2]Myrobalan is a tree whose leaves and barks are widely used as a mordant and also produces yellow, brown or black coloured dyes.

[3] Also called black liquor it is a black liquid consisting of a solution of crude ferrous acetate Fe(C2H3O2)2 usually obtained by treating scrap iron with pyroligneous acid and used chiefly as a mordant in dyeing

[4] Palm jaggery is almost like a jaggery that is made out of sugarcane juice. Palm jaggery is made from the sap extract of Palm Trees in Southern India.

[5] Rubia cordifolia, often known as common madder or Indian madder, is a species of flowering plant in the coffee family, Rubiaceae. It has been cultivated for a red pigment derived from roots.

[6] A small sample of fabric intended to demonstrate the look of a larger piece.

The writers are PhD scholars with National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore.

They would like to thank their colleagues Aparoopa Bhattacharjee, Ashwini K, Shaima Amatulla, Shrestha Mondal and Zarnain Manzoor for sharing their findings with them and their professor Rajani MB for introducing them to the wonderful world of block prints and Tharangini studios.

Contact the one of the authors Sneha Gutgutia