- Hassan has been a hotbed of human-elephant encounters for years and a challenge for forest authorities, who have been translocating crop-raiding elephants for decades.

- An integrated warning system has been replicated from a similar one in the elephant corridors of Tamil Nadu’s Valparai region.

- Fatalities from elephant-human conflict have reduced to nearly zero in the region.

In India, few animals carry the kind of cultural symbolism like elephants do. Human-elephant interaction boasts a rich history dating back centuries. It is but natural that such a long association would also have encounters that do not end happily.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Hassan in Karnataka, the state which is home to India’s largest population of Asian elephants. The Hassan region, however, has been beset by human-elephant conflicts for years with a number of these encounters resulting in fatalities. But, thanks to resilient conservation efforts and smart application of technology in recent months, Hassan could soon be at peace with its elephants.

Hassan and nearby districts sit at the edges of India’s iconic Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and global biodiversity hotspot which accounts for about 60 percent of Karnataka’s forest area. A fertile landscape comprising fragmented forest patches, coffee plantations and paddy fields, Hassan offers a rich and conducive topographical mosaic for elephants, a habitat generalist species known for travelling long distances.

A recent scientific study, published in Tropical Conservation Science in December 2018, on 205 hamlets around Hassan found a peculiar pattern in elephant movement between 2015 and 2017. The paper observed that although the elephants’ numbers were equally distributed between northern and southern areas during their first year (2015-16), their movement was restricted in the second year of study (2016-17).

“Large-scale felling of trees in about 350 hectares of abandoned coffee estates in the central region of the study area and installation of solar fences around these areas restricted movement of elephants toward villages in northern part,” write the authors in the paper.

The barriers have significantly increased human-elephant conflicts as they forced elephants into roads or human settlements.

Jumbos on the move

Authorities and environmentalists had attempted other methods in Hassan from translocating rouge elephants to other areas and building fences, but without any improvement in the situation. Over the years, no less than 100 pachyderms have been captured and moved to other locations but the elephants kept returning. Foresters moved 22 elephants in 2014 alone, but they all made it back to the Hassan area within a short period of time.

At any given point, more than 60 elephants of three different herds roam the Hassan neighbourhood, making encounters with humans inevitable. Elephants use free-flowing travel routes and not strict, narrow areas, said Ananda Kumar, a scientist with the Mysuru-based Nature Conservation Foundation and one of the authors of the study, in an interview with Mongabay-India. For instance, elephants from Hassan could potentially mingle and breed with elephants from Nagarhole National Park and even far-off Coorg.

Also, they show a ‘rotating migration pattern’, he explained. When a herd of elephants is translocated away from the area – like when forest officials moved 22 elephants in 2014 – the herds were shortly replaced by another herd which migrated from farther areas.

An elephant walking next to a farm in Hassan, Karnataka. Encounters between humans and elephants were increasing and about 5 people died each year due to conflicts, between 2010 and 2016. Photo by Ashwin Bhat.

Encounters of the unfortunate kind

A vast majority of elephant-provoked human casualties in Hassan territories – just like in many other elephant corridors in southern India – have been accidental encounters when victims were caught unaware of the animal’s presence in close proximity. Most elephant confrontations occur during the 6-10 AM and 4-8 PM time periods – when workers in coffee plantation and paddy fields are mobile. On an average, elephant-related incidents killed five people every year between 2010 and 2016 in districts surrounding Hassan.

In October 2017, forest authorities introduced a combined early-warning system of SMS alerts, automated voice calls and LED flash-lights at vital public places across the Hassan region. Forest authorities registered over 35,000 mobile numbers for the pre-warning SMS alert system, apart from several local WhatsApp groups. The alerts, in the local language, Kannada, are routinely sent in the mornings and evenings about the possible location of the jumbos, in addition to the warnings on unanticipated elephant presence. Additionally, up to 30 digital display boards in sensitive public junctions caution commuters of the movement of elephants.

The integrated system, which was a result of coordinated efforts by conservationists, government officials and the local community, aims to give just enough information without causing panic or inadvertently helping poachers with details like the strength of the elephant herd or its exact location.

Thanks to the endeavour, fatalities from elephant-human encounters have now been brought down to nearly zero, barring one or two events.

A digital display board in Hassan which alerts people about the presence of elephants in the area. Photo by Ananda Kumar, NCF

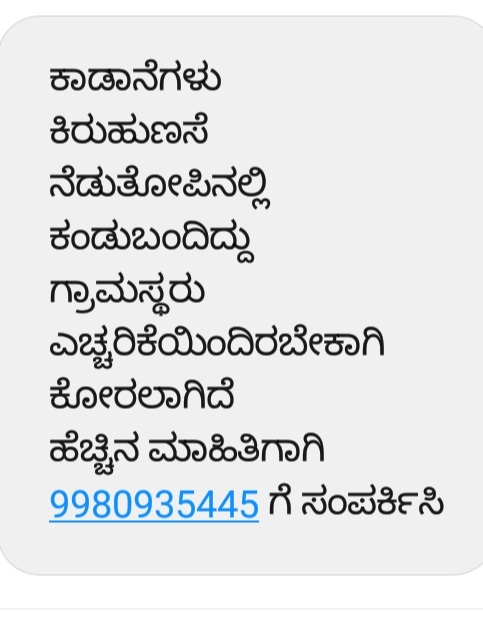

“Wild elephants are observed to be roaming in Kiruhunase estate. Villagers are requested to be on alert. For more information, please contact 9980935445.” Photo from NCF.

The original inspiration

Both the forest authorities and conservationists were reasonably confident of this success since it had yielded satisfactory results in Valparai in the neighbouring state of Tamil Nadu. The Valparai “Elephant Information Network” (EIN) is an early-warning system, which started as alerts on the local television channel but was changed to SMS alerts and display boards in 2011, reduced the average annual human deaths from three to one over these years.

Ananda Kumar, who initiated the EIN and is now working in Hassan, said the Hassan terrain is even more challenging than Valparai. “In Valparai, there are vast company-owned tea plantations whereas in Hassan coffee plantations are owned by individuals. It’s a [more] demanding task to get on board individual owners than to convince companies,” said Kumar.

“Also, there are several small-time owners possessing just one or two acres of paddy fields and not dozens of acres like Valparai. So, if there is damage to crops by elephants, the shock factor on the residents is multifold. This plays a vital role when the local community is a major stakeholder in such projects,” added Kumar.

The warning system in Hassan covers roughly about 700 square kilometres and a human population of 300,000. Of them, 50,000 people live or move in areas where elephants are found.

A beacon installed to alert about elephant activity at a residence in Hassan. Photo by Ananda Kumar, NCF.

“The modus operandi of elephant herds is usually observed by local people and the 150-strong Elephant Task Force before warnings are sent out,” said A.K. Singh, Chief Conservator of Forests at the Karnataka Forest Department. “The fatality rate has come down to almost zero. The two deaths in 2018, after the system was introduced, occurred because the victims ignored the alerts and ventured out despite being warned against it,” Singh added.

Apart from the notification tools, solar fencing has been set up at various locations and routine awareness camps are being organised. In February this year, the Karnataka government allocated Rs 100 crore in its annual budget exclusively to reduce human-elephant conflict by erecting used rail track barriers.

Banner image: An elephant in a paddy field in Hassan, Karnataka. Photo by Vinod Krishnan, NCF.

First published by Mongabay on 5 Mar. 2019