In November of 1909, Mohandas Gandhi was on board the SS Kildonan Castle traveling from London to South Africa. The voyage was a productive one. In just 10 days he penned “Hind Swaraj” on the ship’s stationery. When the book was published in India the following year, the British colonial power banned it as sedition.

“It is Swaraj when we learn to rule ourselves,” Gandhi wrote, setting out how Indians could throw off the foreign dominion and create a more equal society.

Despite India gaining its independence in 1947, the principles of Swaraj set out in Gandhi’s text have never been fully realized. Yet they continue to resonate through Indian civic culture to this day, particularly, says environmentalist Ashish Kothari, in the country’s grassroots environmental movements.

“[Swaraj] is loosely defined as self-rule but it actually goes much deeper,” says Kothari, who has written extensively on Swaraj and the ecological crisis. “It means my own autonomy, self-reliance, self-sufficiency, my independence, both as an individual and as a community. But it’s not the American notion of individualism that I can do what I want.”

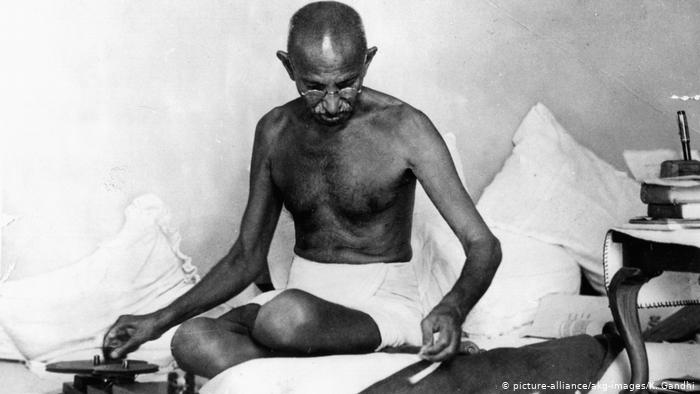

Eco-swaraj has its roots in the principles of swaraj written about by Gandhi in his tract about Indian independence

Radical democracy

Rather, it is a collective kind of autonomy that recognizes our reliance on, and responsibility to, other human beings and other species. As such, living harmoniously with nature is central to Swaraj, Kothari says.

“One has to be respectful of nature and recognize that other species and Earth as a whole also have rights in their own entity, not just because they’re useful for human beings.”

“Eco-Swaraj” is not a movement itself, but Kothari uses the term to describe patterns he has observed in hundreds of initiatives across India that are fighting destructive development, such as dams and mining projects, as well as those building sustainable alternatives. In every instance, citizens are the driving force for a bottom-up approach.

“One of the fundamental tenets of eco-Swaraj is radical democracy, which means power at the level of ordinary people,” Kothari says. “It’s not about a government laying down policies. It’s really about everybody. Every person in a village builds the capacity to be centrally part of decision making.”

From tenant farming to food sovereignty

That has helped thousands of women in India’s Telangana state transform themselves from food seekers to food providers. Before the Indian agricultural NGO Deccan Development Society (DDS) was founded in 1983, many families in the state’s Sangareddy district struggled to get enough to eat. Men and women mostly worked for meager wages as agricultural laborers on other people’s land, while their own smallholdings lay fallow.

Sangham members donated 20,000 kilograms of grains to supply a nutritious millet porridge twice daily to workers in villages during India’s coronavirus lockdown

DDS encouraged women to form sanghams, or self-help groups, to discuss food security and come up with solutions. They borrowed seeds from neighboring villages and revived traditional crops suited to the soil and arid climate.

The 3,000 women sangham members are now organic farmers, growing up to 35 different crops — such as millet, pulses, oilseeds and wild greens — on every acre of land, and they also have their own seed bank of 80 varieties. During India’s coronavirus lockdown, each member donated 10 kilograms (22 pounds) of millet to cook a nutritious porridge for hundreds of healthcare and sanitation workers.

“Before the sanghams, they were alone, they were individuals,” says Jayasri Cherukuri, co-director of the DDS. “Now, when they are doing things collectively, they get more courage to speak about the issues they are facing.”

Cherukuri says women who were afraid to confront their landlords are now demanding a place on local government committees. And it isn’t only rural communities speaking up on decisions that affect their environment.

Reviving traditional technology to preserve water

Residents of the Shivram Mandap slum collectively manage a system that pumps water from a well to a water tank and is then distributed to the entire area

In the city of Bhuj in western Gujarat, residents’ collectives are coming up with their own plans to manage waste and drinking water, which they take to government officials for funding.

Borewells have depleted Bhuj’s groundwater, resulting in alternating water shortages and flooding. In contrast, these resident-led projects are sustainable; they are bringing back the city’s traditional system of recharge wells to replenish groundwater, cleaning up polluted lakes, and harvesting rainwater at all schools and colleges.

The collectives are coordinated by Homes in the City, an NGO that has been working with slum-dwellers in Bhuj for the last decade. “Before, citizens were limited to voting for elected officials and thinking that they will take decisions about the city,” says Aseem Mishra, program director for Homes in the City. “We are trying to change citizens’ mentality that you are part and parcel of city development.”

Diverse solutions for local contexts

One of the advantages of localized, grassroots initiatives over top-down organization is that it is shaped by local traditions, and local ecology.

“Every region and every culture has its own tradition and understanding of nature,” says Brototi Roy, a PhD candidate researching environmental justice movements at The Autonomous University of Barcelona. Eco-Swaraj recognizes that this diversity means adapting to local contexts rather than imposing one-size-fits-all solutions.

Members of the Bhuj Ward Committee No. 2 gather at the ward office for their meeting. Bottom-up grassroots initiatives are better suited to local ecology and traditions

Kothari says eco-Swaraj also has strong parallels in other parts of the world, such as the concepts of Ubuntu (“I am because we are”) in Africa, Buen Vivir (“good living”) in South America, the Zapatista Autonomy movement in Mexico, and Abwicklung des Nordens (“Undeveloping the North”) in Germany.

With shared values of autonomy, social justice and living in harmony with nature, these frameworks are being used to challenge a mainstream approach to environmental problems rooted in “development” — the idea that the Global South should strive to emulate the richer economies of “developed countries” in the Global North.

Resisting imperialism, then and now

Gandhi wasn’t the first to apply Swaraj to the struggle for Indian independence. It was already central to 19th century resistance to British imperialism and the idea has far older roots on the Indian subcontinent, which was host to some of the world’s earliest democracies as far back as the 6th century BCE.

Now, activists like Kothari are using the idea to frame alternatives to “the tendency of ‘modernity’ and ‘developmentalism’ to shape the whole world in a homogenous western, consumerist, materialist frame,” as he says in a 2018 paper.

Eco-swaraj espouses an alternative development path to the ‘western, consumerist’ frame

Mainstream environmental fixes might target carbon emissions, plant more trees or rely on an app to manage resources, Roy says. But this does not fundamentally alter a system in which environmental and human health are fighting a losing battle against economic development.

“When we consider people and planet over profits, resources are managed by local participation and we can get to an ecologically benign way of living,” she says.

First published by Deutsche Welle on 20 Aug. 2020