August 7 was National Handloom day —but the handloom sector still faces huge challenges. Smart policy and supportive industrialists could help create a real fair trade culture.

On August 7, 1905, several prominent leaders of India’s freedom struggle — Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Aurobindo Ghosh, Bipin Chandra Pal and others — sparked off a Swadeshi Movement demanding that Indians boycott all British mill-spun yarn and cloth in favour of native handmade products. Khadi became a totem of the Independence movement and handloom weaving an exemplar of self-reliance. To mark the occasion, it was decided in 2015 that August 7 would henceforth be designated National Handloom Day.

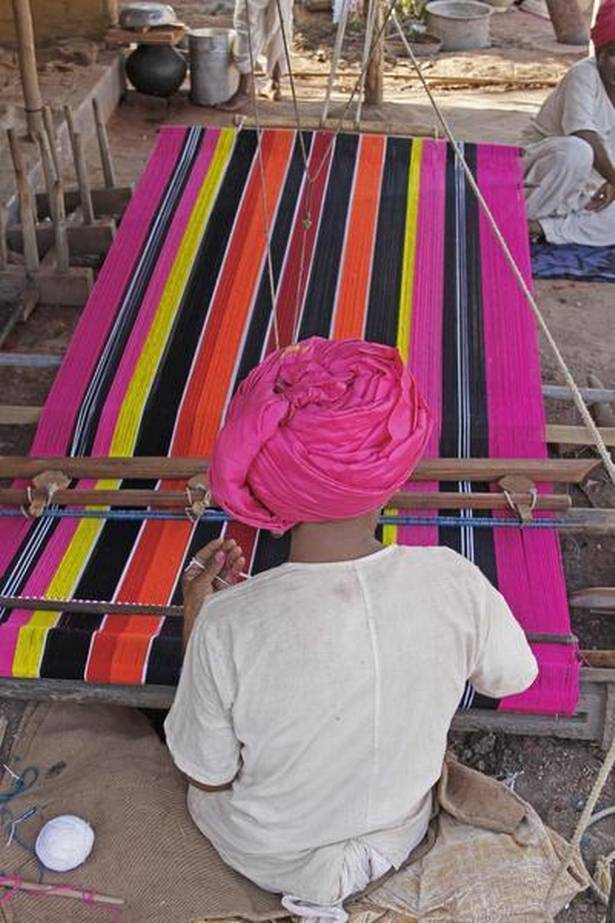

India’s handloom sector is the second-largest employer in the country after agriculture, employing more than 43 lakh people. The craft of manual weaving and the loom process along with natural and organic processes of creating textiles are unique to the Indian subcontinent. Some of them, like the Bandhani tie-dye technique, have been dated back nearly 5,000 years to Mohenjodaro and Harappa.

The sheer range of fabrics produced across the country is dizzying. From Kashmir in the extreme north to Kanyakumari in the south, every region has its own signature weave. Books can be written about just the silk varieties — from the Bhagalpuri silks of Bihar to Kosa of Chhattisgarh to Jharkhand’s Kuchai, Mysore silks, Paithani of Maharashtra, Eri silk of Meghalaya, Muga silk of Assam and Tamil Nadu’s famous Kanjeevarams — each one with its own history and pedagogy.

Chinese imitations

Global fashion markets today are inundated with factory-produced fabrics and synthetic materials. In India too, the handloom industry runs the risk of being overshadowed by the well-funded mill and power loom sectors.

Apart from local competition — power looms now supply more than 70% of Indian textiles — Indian weavers face the threat of machine-made Chinese imitations flooding local markets; Chinese pashminas, Chikan embroidery, Banarsis and imitation Kutchi mirror-work are widely available in India.

In the case of the celebrated pashmina shawls, the situation is so dire that shawl manufacturers in India actually import raw pashmina from China and Mongolia; only 1% of the global supply of pashmina is sourced from India. Lack of a fair trade culture often leads to crushing exploitation of highly skilled artisans. An original pashmina shawl retails at $300–$400 depending on the level of craftsmanship, while a Kani shawl from the same region starts at $800, but local producers are paid less than $2 per day for up to 10 hours of hard labour.

The designer and activist-entrepreneur Laila Tyabji started the Dastkari bazaars in 1982 with a view to bridging the gap between craftspeople and urban buyers. Here, rural artisans, many of whom had never encountered urban customers, were provided with the means to enter the mainstream retail chain. Dastkar has a policy of leaving the ownership of the goods to the artisans, while retaining 10% of the revenue for operational costs.

A game-changer at the time of its inception, the idea has been replicated many times since. Today the organisation works with 700 artisan groups, employing over one lakh people. A similar enterprise, the Dastkari Haat Samiti, was launched by former politician Jaya Jaitly in 1986 to showcase handcrafted products sourced from across the country and to promote artisans at an annual crafts bazaar.

In Tyabji’s view, the government’s much-touted ‘Make in India’ programme could be most efficiently harnessed for traditional arts and crafts rather than blindly aping western tropes of modernisation. “The ‘modern’ skills currently being expensively promoted encourage wholesale migration to India’s overburdened cities, placing a further load on our already inadequate urban infrastructure,” she said in an earlier interview. “On the other hand, textile skills are based in rural India, with minimal carbon imprint, perfectly suited to rural production systems and social structures. They also bring agriculturists and rural women into the economy, creating double-income households in otherwise poverty-stricken areas.”

Indigenous skills

Tyabji has a knack of getting to the heart of the matter: “Politicians, bureaucrats and economists, trying to turn us from ‘developing’ to ‘developed’, need to recognise the value of existing indigenous technologies, skillsets and knowledge systems. If we can do it for yoga, we can surely do it for handlooms, which would benefit hundreds of millions.”

One of the challenges facing the industry is the unwillingness of the younger generation to take up ancestral crafts. “In a globalised world, legacy, culture, heritage and similar words only mean something for the educated and the enlightened,” says Shailin Smith,director at Raj Group, a purveyor of high-quality handlooms to the international market. “Aspiration is usually more influential than the responsibility of being bearers of culture. The threat therefore lies in the current generation practising the craft. If they do not take pride in what they do, they won’t be willing to impart it to the next generation.”

The Raj group has factories in Panipat and employs over 6,000 weavers, many of whom are the second generation in their family to work with the company. They also run Bal Vikas, a school established to provide education for children of weavers and workers. The company actively promotes the art of manual weaving through its various projects, notably the Raj Arts initiative. “The art initiative envisions projects that create a cross-cultural experience for the weavers and help instil a sense of pride in their craft,” says Smith. “We tend to work with international artists who would like to experiment with the craft and integrate its processes into their form and aesthetic.”

Towards this end, Raj Arts organises artist residency programmes facilitating the creation of site-specific fine art installations and transformation of textiles into bespoke art pieces. During the residency, the artist and the weaver both cross class and cultural barriers to merge into one line of creative thought to produce a work of art.

Industrial responsibility

In Smith’s view, the responsibility to preserve and promote cultural legacies falls on industrialists and the private sector rather than the state. “I feel that the industry that derives from any craft should be the actual custodians to preserve it. Like the Raj Group, other industrialists should also be able to promote the craft beyond consumerism and sensitise all stakeholders. Our (industrialists’) responsibility should be to protect, document and promote our craft forms. And when any form ceases to exist, we should have amply documented it to revive it.”

A case in point is the iconic brand Fabindia, which played a big role in the transformation of indigenous crafts, khadi and handlooms from a quasi-political movement into a trendy fashion statement. Founded by the American, John Bissell, in 1960, today the company is India’s largest private platform for products made from traditional and hand-based processes. It has 226 shops across India and more in Singapore, Dubai, Malaysia, Mauritius, Nepal, Rome and Dallas, USA. In addition to market access, the company provides its artisans with training, needs-based financial aid and raw material. Today the company works with 55,000 artisans from across the country, and declared sales of ₹911 crore (roughly $130 million) in 2015–2016.

India has some distance to cover before its artisanal goods are treated on par with counterparts abroadbut with smart policies and adequate grassroots support, it could get there in the foreseeable future. More importantly, an entrenched fair trade culture could go a long way in providing highly skilled indigenous artists with the compensation, dignity of labour and professional pride they so richly deserve.

First published by The Hindu on 11 Aug. 2019