One day about seven years ago, I visited one of the infamous photocopy shops near Delhi University’s south campus. I had just enrolled in a master’s course in literature at the university and needed to buy textbooks. The shop sold pirated photocopies of DU’s prescribed readings at about one-tenth the price of the original books, which were out of reach for most students.

I remember standing at the shop, flipping through the syllabus. It was clear why the course was called “English literature” and not “literature in English.” There was “Poetry from Chaucer to Milton,” “Eighteenth-century English literature,” “Seventeenth-century English drama” and an entire paper on Shakespeare. By contrast, there was just one compulsory paper on Indian literature, summing up thousands of years of literary output in four short texts.

I recalled an essay by VS Naipaul, “Words To Play With,” on the education he received in Trinidad. Naipaul complained of having to endure William Wordsworth’s daffodils and Charles Dickens’ London rain. There were no daffodils in Trinidad and instead of rain, the Caribbean island had tropical downpours. Every piece of literature he read at school became a work of fantasy, as “we could not hope to read in books of the life we saw about us” and, further, that “until they have been written about, societies appear to be without shape and embarrassing.”

Fifty years after Naipaul wrote that essay, it is still relevant in contemporary India. In my years spent studying literature from that photocopied material (rather apt since the course drew so heavily upon the curriculum in the United Kingdom), I was amazed at how little of the life around me was illuminated by this education. In time, I also realised that the reason I had read literature produced in and about another society was because the university system did not consider literature produced in India to be the real thing.

What ought to be given the status of knowledge, and thus deemed worth studying, is a deeply political question for any society. While many writers and authors, from Rabindranath Tagore to the poet and scholar AK Ramanujan, have taken up this issue, there are few who have delved as deeply into it as the scholar Ganesh Narayan Devy. Over his four-decade-long career, through books and papers written at the intersection of linguistics, literary criticism and anthropology, Devy has consistently questioned the terms on which knowledge is produced and consumed. Recognition for Devy has come from several quarters: a Sahitya Akademi award, a SAARC Literary Award, the Prince Claus award, the international Linguapax prize and the Padma Shri, among many others. And yet his name can evoke blank stares, even among those within academia.

The cornerstone of Devy’s work has been an examination of the links between knowledge and power, and the monopoly on knowledge by the elite throughout the course of human history. He wrote in the essay “The Being of Bhasha”: “The Barbarians do not have knowledge, the Romans have it. Those who speak or recite Sanskrit have knowledge; those who speak Prakrit have no knowledge. Those who speak English have knowledge, those who do not have no knowledge worth the name. Such is the political context of every knowledge system.”

Devy’s latest book, The Crisis Within, published last year, is his first in-depth engagement with the implications of this elitism for India, making it relevant for our understanding of disciplinary fields across the arts and sciences. It details the ways in which the worldviews of the disempowered have been historically destroyed in India through a deliberate sidelining of their languages, and it calls for a reassessment of what counts as knowledge in every field. Indigenous in its emphasis on alternate knowledge systems and yet cosmopolitan in its openness to the mainstream, Devy’s book is seen as a communist manifesto of sorts for Indian languages and their associated knowledge systems, seeking an equal status for all.

There is no better illustration of the power of Devy’s ideas than the story of his life, most of which has been spent in the dogged pursuit of suppressed knowledge. He has practised stubbornly and heroically what he has preached, even in the face of adverse consequences.

I visited Devy and his wife Surekha in Dharwad in early December last year, on a day when the small town in north Karnataka was celebrating Eid-Milad. One of the first things that struck me was the number of books in their home. The light-coloured walls of their living room and dining area were lined with shelves holding books in more languages than I could identify. “We moved in here with just the books,” Devy, dressed in a plain white shirt and trousers, told me as we spoke over a breakfast of poha.

This shift to Dharwad two years ago might seem odd for a 66-year-old scholar who had till then spent most of his life in Gujarat and Maharashtra, and is only now learning Kannada. Devy explained to me the many reasons for the move. For one, there is the rich cultural legacy of Dharwad, of which most Indians outside Karnataka are unaware. The town, besides being a hub for Hindustani classical music, has produced several writers, scholars and artists. Three writers from Dharwad—Girish Karnad, DR Bendre and VK Gokak—have won the Jnanpith award. Musicians associated with the town include Bhimsen Joshi, Sawai Gandharva, Bal Gandharva and Gangubai Hangal.

But there was a stronger reason that brought Devy and Surekha to Dharwad. In August 2015, the well-known scholar and writer MM Kalburgi, also a Dharwad resident, was murdered in his own home, apparently for his criticism of religious orthodoxy. Devy was appalled that the Sahitya Akademi cared so little about the assassination of a noted writer that they did not even release a statement about it. That October, Devy returned his Sahitya Akademi award in protest. In March the following year, he moved to Dharwad to handle the legal fight for justice for Kalburgi. Referring to other writers and activists killed in recent times such as Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare, Devy said, “Pansare had his party. He was a member of the communist party. To support him, Dabholkar had this organisation called Maharashtra Andhshraddha Nirmoolan Samiti. But Kalburgi stood alone. He has no such organisation to back him up. So I thought I’ll come here and provide that support.”

Devy’s life, which he took command of quite early on, is shot through with deep idealism and determination. He was born in Bhor, a village about fifty kilometres west of Pune. His family, being Gujarati, hired a tutor to teach him how to read and write in the language. But the education was cut short when the tutor moved away. One day, at the age of five, he told me, he came upon a government-run Marathi-medium school as he was strolling around the village. He simply walked in and started attending classes. “It was not first-standard classes, but second-standard,” he said. “In those days such things were possible in India.” Before he was ten years old, his father’s small trading business had gone bust and “the family had no money.” From the age of 12, he had to fend for himself and fund his own education. He held several menial jobs, being a porter for a time and then a street vendor. “But none of that left a scar on me,” he said. “I was always a happy child … Not in terms of the pleasures I had, but in terms of the peace I had. There were immense hardships but I was happy. I have been at peace with myself.”

Devy enrolled in an English-medium science-stream junior college in Pune after he had completed the tenth standard. “There, everything was in English,” he said. “I was not comfortable with that. I understood what they taught but I could not speak. So I dropped out.” His parents were separated by this time, and neither of them interfered with his decisions. He moved to Goa and did a stint as a labourer in a mine, also starting to read English books to improve his facility with the language. “I decided that I will read two to three hundred pages every day.” He began with the popular authors of the day—RK Narayan, Pearl S Buck, Arthur Koestler, among others. He enjoyed reading fiction so much that he decided to study literature formally, and enrolled in a college.

“I used to read round the clock,” Devy told me. The librarian at the Shivaji University in Kohlapur, from where he took his master’s degree and PhD, allowed Devy to spend nights at the library. Devy chose the works of Aurobindo Ghose, better known as Sri Aurobindo, as the subject of his PhD thesis. This was an unusual choice. “Normally, at that time, dissertations would have titles like ‘India in Shakespeare’ or ‘Milton’s impact on Wordsworth’ or some such thing,” he told me. Aurobindo’s attempts to combine Indian thought with Western ideas drew Devy to him.

It is hardly surprising that he and Surekha met at the library. Devy told me he asked Surekha to marry him the first time he saw her. Surekha agreed and they got married while they were both pursuing their PhDs (Surekha studied chemistry). He refused to accept dowry from Surekha’s parents, telling them that if they insisted on a gift, they could give him the complete works of Aurobindo.

After getting a PhD, Devy qualified for the Rotary Foundation fellowship, which allowed him to attend a university of his choice anywhere in the world. He decided to go to the University of Leeds for a second master’s degree and wrote a thesis on the work of the poet, translator and anthropologist AK Ramanujan. In 1980, Devy began working as a lecturer in English at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. Over the next decade, he won several fellowships and scholarships while meticulously researching Indian literature and literary criticism, work that resulted in iconic books such as After Amnesia, published in 1992, and Of Many Heroes, published in 1997.

In 1987, a severe drought hit many parts of India. Gujarat and Rajasthan were worst affected. Devy, who was teaching at the university and also running a bilingual Gujarati-English journal at the time, decided to try and help. He formed a group of 120 students who took up relief for 30 villages, the farthest one being 110 kilometres away. During the week, the group would raise funds to buy foodgrain, fodder and medicine. On weekends, they went out to the villages to distribute these goods. The group swelled as people from outside the university joined it. Devy sustained it for a year, but the vice chancellor of the university took exception to Devy’s activism and ordered him to stop the relief work. Devy protested and went on a hunger strike. This resulted in a court case that lasted for about two years. Devy wrote the final chapter of After Amnesia—arguably one of the most important works of Indian literary criticism—on a typewriter while sitting under a tree outside the Baroda court.

In Kalidasa’s play Abhigyanashakuntalam—The Recognition of Shakuntala—Dushyanta, the king of Hastinapura, chances upon Shakuntala at the hermitage of the sage Kanva. He woos and marries her but then has to go away to attend to his kingdom’s affairs. He gives Shakuntala a ring as a token but on her way to the palace, she loses it. To make matters worse, a curse makes Dushyanta forget Shakuntala. The king does not recognise his queen in Hastinapura, and when she goes back to her hermitage, she is abandoned by Kanva as well.

While the play eventually ends happily, it is this turn of events that Devy finds interesting about the story. The relationship between Dushyanta and Shakuntala is an archetypical representation of colonisation, he writes in After Amnesia. Shakuntala (the colonial subject) leaves the hermitage (her own cultural context), but finds herself rejected by Dushyanta (the colonial oppressor) as well. Devy believes the story provides an excellent metaphor for the situation of literary critics in India, many of whom abandoned their cultural context and deluded themselves into thinking they were part of a Western intellectual tradition, to which they had limited access. Colonialism turned Indian intelligentsia into a society of amnesiacs.

Devy argued that the colonial encounter had a two-pronged effect on Indian literature and literary criticism. Certain colonialists, such as Macaulay, argued that Western literature and intellectual thought were inherently superior to the Indian literary tradition; in response, sympathetic liberal orientalists said that though India may be a civilisation in decline, it had produced great literature in the ancient period. Devy suggests that the debate between westernised Indians and nativists today echoes that older nineteenth-century one. Those who argue for the Sanskritisation of Indian culture, fuelled by their fantasies about the ancient past, have way more in common with the orientalists than they think. However, both westernised Indians and nativists agree on one questionable assumption: that contemporary Indian thought holds no inherent value. As a result, literature and literary criticism in the “bhashas”—the numerous vernacular languages of India—produced from 1000 CE till the arrival of the British have been more or less forgotten. As if reminding long-time amnesia patients about their loved ones, Devy outlines the intellectual accomplishments of the immediate precolonial past, while also acknowledging the existence of adverse social conditions at the time:

Seventeenth-century India presents a record of highly impressive achievement in arts and literature. The contributions to music, painting, dance, architecture and poetry made during this period form a glorious chapter in Indian history. Yet, no simple formula of the relationship between living cultural traditions and great social problems can explain the entire period satisfactorily. One encounters a paradox difficult to explain. Side by side with the emergence of a novel Marathi poetics in Tukaram’s (1598–1649) redefinition of the Hindu world view, one finds Jagannatha (1620–65) concluding the long, tired line of Hindu poetics in Sanskrit. On the one hand is seen the development of a novel literary genre like Assamiya Buranji, on the other the faltering progress of the Bhakti school, created so ably in the preceding century by Mira (1498– 1573), Kabir (1440–1518) and Tulsidas (1532–1623).

After Amnesia won the prestigious Sahitya Akademi award in 1993, the first English-language work of literary criticism to do so. Devy’s popularity rose, and he started getting invited to lecture at universities across the world. In the foreword to The GN Devy Reader, a collection of Devy’s essays published in 2009, the scholar Rajeshwari Sunder Rajan writes of the academic work on Sanskrit and bhasha literatures by a range of leading scholars, including DR Nagaraj, Sudipta Kaviraj and Harish Trivedi, that has appeared since Devy’s book: “They could not all have been known to Devy at the time of course. But the mere fact of the existence of such works today, even apart from their excellence, is a validation of the revisionary Indian literary history and criticism that Devy was developing twenty years ago.”

Some of the responses to After Amnesia were critical—writers such as Francesca Orsini, Harish Trivedi and Vasudha Dalmia pointed out that Devy had not demonstrated how present-day literary criticism can be revitalised by looking to the literature of the immediate past, and they objected to what they saw as a complete rejection of Western poetics. Meanwhile, Devy himself has moved on from the “nativism” of After Amnesia. “I used to be interested in discovering the ‘Indian’ way of looking at things,” he told me. “Now I find that restricting. I am interested in all kinds of approaches, Indian or not. I don’t think nations are a very lasting category.”

Nevertheless, After Amnesia remains a pioneering text which undoubtedly contributed to changing attitudes towards India’s ancient and contemporary literature. “Devy’s energetic and stimulating book marks a flying start to what clearly will unfold as a brilliant career in criticism,” Trivedi wrote in the journal Indian Literature in 1994, “in the course of which works of greater substance, gravity and mass are sure to follow.”

Devy could, indeed, have followed that path—written a few more scholarly tomes or maybe moved to the United States, as many Indian theorists do. But the conclusions he had reached in After Amnesiapulled him in a different direction.

In works such as A Nomad Called Thief and “The Being of Bhasha,” published in 2006 and 2009 respectively, Devy developed a view of knowledge and language that differed remarkably from the most prominent strands in Western critical theory.

The best known proponent of the idea that knowledge is power is the French philosopher Michel Foucault, who, in his book The History of Sexuality, argued that unequal relations between the oppressors and the oppressed—men-women, rich-poor, white-black—produce knowledge. The purpose of knowledge, he argued, is either to reinforce or challenge these all-pervasive, dominating structures. Many scholars of postcolonial theory were deeply influenced by Foucault, and they largely upheld his idea of the power-knowledge relationship. Edward Said, in his landmark book Orientalism, critiqued the concept of “the East” created through cultural representations in the Western world, and the work of other postcolonial theorists such as Homi K Bhabha, Gayatri Spivak and Dipesh Chakrabarty has followed on from this idea. While this theoretical output produced useful critiques of Western discourse, its authors have been wary of any revisionist or nativist projects, fearing that this would create “essentialised” or fixed identities of the colonised nations.

The cultural influence of Foucault’s ideas cannot be overstated. Many academicians, writers, artists, journalists and even Facebook and Twitter commentators today are knowingly or unknowingly his disciples. Critical analyses of all aspects of culture along the lines of oppressor-oppressed relationships in categories such as gender, race, class and caste groups are ubiquitous on all kinds of media. Any piece of cultural production must first pass the test of whether it “punches up” or “punches down.” Rules on who can write about whom and charges of cultural appropriation have their roots in post-structural and postcolonial theory.

Devy’s approach is an interesting departure from this tendency. While knowledge is influenced by power relations, it has also, historically, had other objectives, he says: the primary ones being survival, social harmony and the preservation of collective memory. Devy has not focussed solely on undermining concepts that further the interests of power, but on recovering suppressed knowledge that could serve creative and constructive functions beyond the realms of oppression and resistance.

For Foucault, no worldly experience, no access to reality, is possible outside of knowledge, power and language. Devy disagrees. In “The Being of Bhasha” he writes, “There are experiences that the human animal shares with other animals that show a marked absence of language based on sound regulation. Vertigo, or the fear of falling, and love or sensuous attraction are the main instances of such experiences.” Further, he believes that language and reality have a complex relationship in which they are forever altering each other.

It is the creative potential of language that Devy wants to harness. Alienation from bhasha is singularly tragic, he argues. With the loss of language, one loses the history of negotiation between that language and the reality from which it has evolved. The loss of language is the destruction of a system of knowledge. Devy’s views are reminiscent of those of the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiongo, who in his book Decolonising the Mind, wrote:

Language as communication and as culture are then products of each other. Communication creates culture: culture is a means of communication. Language carries culture, and culture carries, particularly through orature and literature, the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in the world.

But Devy goes further by distinguishing between formalised, static languages and the ever-evolving dialect, which is in closer proximity to knowledge:

… to be a dialect, is not being left behind, but to be avant-garde, to be on the forefront. If we imagine a certain component of language (as a substance within the system that it is) whose destiny it is to be at the turbulent interface of the ever expanding reality, and if we imagine that this component is required to persist in its work without losing its identity as language—be in currency at least with the value of counterfeit—we will have imagined a dialect.

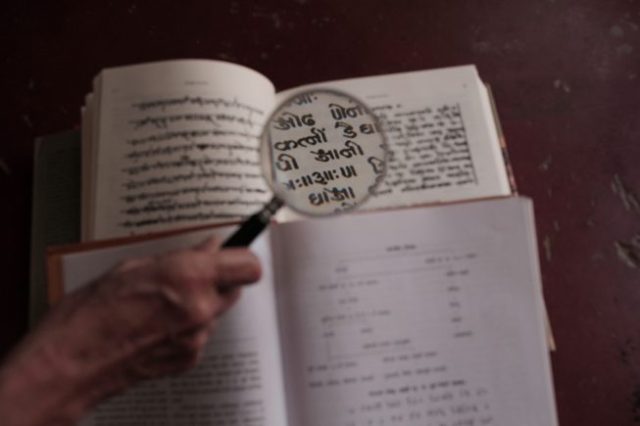

According to Devy, knowledge can only be expanded at the margins of experience, which is why he chose to study bhasha over the poetics of Sanskrit, and Adivasi literature over that of the dominant castes. It is also why he argues that each dialect, spoken by however many people in whichever part of the country, needs urgently to be preserved. Devy’s work in the last two decades has been centred on just such a mission.

Just as British political dominance sidelined the major Indian languages, the political dispensations since have marginalised the country’s Adivasi languages. Devy explained in a video interview with Scroll.in, “The 1961 census had listed 1,652 mother tongues. The data of 1971 showed only 108 mother tongues.” Devy said he was curious about what became of those 1,500-odd languages. Plotting the missing ones on a map of India, he found that most of them were spoken in the central part of the country, the zone separating the Indo-Aryan languages from the Dravidian ones. “This zone is populated by tribal communities,” he said, “roughly running from Surat to Howrah, if you were to draw a straight line on the map of India.”

In 1995, at the height of his success as a critic, Devy decided to give up his university job and move to Tejgadh, a village in Gujarat that is home to the Rathwa tribe. He travelled from village to village with a notebook and tape recorder to document and study these languages. “I no longer felt comfortable to draw a salary teaching English literature when languages were dying around us,” he told me.

In Tejgadh, Devy founded the non-profit Bhasha Research and Publication Centre to study and document India’s cultures and languages. Activism in the form of healthcare projects, microcredit, foodgrain banks and water collectives—in Tejgadh and nearby villages—went alongside linguistic and cultural documentation. Three years after starting the foundation, in 1999, Devy launched the Adivasi Academy in Tejgadh as an “unconventional learning space.” The academy was meant to do for Adivasi culture, arts and literature what libraries, museums and national academies had been doing for mainstream culture. Around the same time, he collaborated with the writer Mahasweta Devi to form an organisation to fight for the rights of denotified and nomadic tribes, or DNT, who were listed in the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 and were later labelled “habitual offenders” by the Indian government in 1952.

“I stopped reading books,” Devy told me. “I started educating myself again.” During the 2000s, he travelled widely across tribal areas. A article by Nandini Nair in Open magazine documented the various projects he undertook at this time, including putting out journals with songs, epics and folklore in several languages such as Knukna, Ahirani, Bhantu, Pawari, Rathwi, among others. These journals, copies of which are still on Devy’s bookshelves, would be sold at nominal rates to the tribal communities whose culture they documented. Devy devoted that entire decade to working in tribal studies.

His 2006 book, A Nomad Called Thief: Reflections on Adivasi Silence, is an account of this time—its title refers to the DNTs. Early on in the book Devy provides a “random list of what we have given the Adivasis” over 60 years of Independence. It reads: “Forest Acts depriving them of their livelihood; a Criminal Tribes Act and a Habitual Offenders Act; … existence as bonded labour; forest guards and private moneylenders; mosquitoes and malaria; naxalites and ideological war-groups; … and perpetual contempt.” At first glance this reads like a damning indictment. But Devy does not constantly reprimand, he states facts. He addresses the mainstream to convince them of the value of letting Adivasis speak.

His Adivasi Academy—with a library of roughly 50,000 books (many on tribal culture), a museum, a multilingual school and a health centre—illustrates his approach. After setting up the place and training the manpower drawn from the local community, Devy withdrew from the management of the Academy. That was always the plan, he told me.

Even as Devy quit his job to pursue activism full-time, Surekha continued to work as a professor to support the family. Any money Devy raised went to the non-profits he had founded. He gave the entire sum of 25,000 euros he received from the Prince Claus award in 2003 to the Bhasha Centre, despite the fact that the family was in financial need. Surekha did not complain. “It takes courage to live like this, in simplicity,” Devy told me in his characteristic matter-of-fact tone. “I am glad that she has that courage.”

At about three in the afternoon, when we had been talking for over four hours, we decided to break for lunch, which was a home-cooked thali in the style of Dharwad’s famous Khanavali canteens.

In 1886, the British administrator George Abraham Grierson proposed a survey of India to document all its languages. Grierson was appointed the superintendent of the Linguistic Survey of India. His project lasted 30 years, from 1894 to 1927, and described a total of 364 languages and dialects. The survey’s findings have been criticised for their supposedly flawed methodology and for excluding large parts of contemporary India. No Indian government has undertaken such an exercise since. Though the United Progressive Alliance government announced it would carry out a similar survey, and allocated Rs 2.8 billion for it in the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007–12), the project never took off. Devy had been stressing the need for the survey for years, arguing that documentation was essential for the survival of endangered languages.

When the government abandoned the project, Devy decided to do it himself. In 2010, he began putting together the team that would conduct the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, or the PLSI. This was a group of over 3,500 volunteers, which included academics, schoolteachers and anyone willing to help. Devy utilised every single contact he had built during his travels over the years. Between mid 2010 and the end of 2011, he undertook 300 journeys, holding workshops in different states on how to conduct surveys. By 2013, Devy had created multiple coordinators for every state in the country and had put together a national editorial collective of 80 scholars.

On 5 September 2013, Devy asked three coordinators from each state to bring their work to a meeting at the Gandhi memorial on Tees January Marg in Delhi. “I asked them to place their manuscript on the ground as dedication to the nation,” he said. “Every state and every Union territory. They came. And 30 volumes in manuscript were placed there.” He had chosen 5 September because it was the birthday of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan—the second president of India who was also a scholar—now celebrated as Teacher’s Day.

The publishing house Orient BlackSwan agreed to publish the volumes. Devy estimates there will be about 92 books in the PLSI, 45 of which have been published and the rest of which will be out by 2020.

The PLSI’s findings boggle the mind. The survey found 780 languages in the country. For each language, the books provide a brief history, the geographical region where it is spoken, samples of songs and stories with translations and important terms in the language. To anyone wishing to learn about the lived experience of different segments of Indian society, these volumes are invaluable. As a BBC article on the PLSI reported, the survey found that some 16 languages in Himachal Pradesh have 200 words between them to describe snow, with specific expressions for “snowflakes on water” and “snow that falls when the moon is up.” Nomadic communities from the deserts of Rajasthan also use a large number of words to describe the barren landscape, including separate ones for how men and animals experience the “sandy nothingness.”

According to Devy’s theory of knowledge, this means that there are 780 ways of understanding this country, 780 separate repositories of knowledge that deserve equal status. And how many does the Indian state acknowledge? Twenty-two. Speakers of hundreds of Indian languages find no schools that teach in their mother tongues and no economic opportunities to use them. Documentation, as Devy says, is the first step towards that equal status.

The PLSI gives us a sense of the scale of India’s many epistemologies, and yet, most educational and professional institutions view knowledge as that which is generated in the few prominent languages that have state recognition. These are languages spoken by a handful of dominant groups. Social structure, language and knowledge are interconnected, Devy points out in his latest book, The Crisis Within.

On the social level, a hierarchical view of class, caste and tribes has narrowed down the idea of knowledge. “In India higher education has managed to lose touch with lifestyles and histories of exclusion of the communities,” Devy writes, referring to oppressed castes and tribes. “And therefore, one is not able to fully access the idiom through which life is perceived outside our campuses.”

In turn, English remains dominant because of the “continued knowledge imperialism of the West.” Globalisation and the opening up of the international labour market have made a certain kind of knowledge marketable. Since America is the most celebrated site of globalisation, American or Americanised education holds great value. Top department heads and editors—commissioning research projects and books—are often products of elite schools or foreign universities. An editor who leads a reputed media organisation recently told me that his team found it difficult to do stories about indigenous subjects, such as Hinduism and Hindutva, simply because most of the editors had had a Western liberal education and are not very familiar with the discourse.

Devy offers an interesting diagnosis. He told me that the development of print as a medium in Europe was linked closely to the rise of the middle class towards the end of the medieval period. It is not coincidence that many iconic works that have added to our knowledge were not meant for publication, he told me. “Shakespeare, Tagore, Kabir—they were all poets and dramatists,” he said, whose works could have been delivered orally. “Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste was also meant to be a speech.” Magazines, newspapers, books are the product of a knowledge industry whose job is to keep the middle class steady and secure, Devy said. “A truly great iconic production of knowledge that can change society is not possible within that range.”

The crisis within, then, is a crisis of creativity in our institutions. Our linguistic prejudice, which stems from our social location, makes us blind to the astoundingly multifarious nature of our surroundings. Like many other scholars, Devy has come to believe that developments in technologies of transmission will render traditional educational institutions obsolete. What we wish to learn will be available to download. As we enter this new phase, we must give serious thought to what kinds of knowledge we are going to carry over.

The answer, according to Devy, isn’t just diversity and creating “inclusive spaces.” Museumising “diversity” and “hybridity” would be useless without a democratisation of knowledge. The creative interchange between cultures, hailed by many scholars as a mark of great modern literature, has to take place on a level playing field if charges of appropriation are to be avoided. “In India, the ‘marginalized’ far outnumber the dominant sectors of society,” Devy writes in The Crisis Within. “The country’s ‘mainstream’ can only be an aggregate of the margins.”

Devy also said that we must not think that we are doing the marginalised any favours by recognising them. “The question of ‘inclusion of the excluded’ should no longer be seen as a question of grudgingly giving something because it’s politically correct,” he writes. “But rather as an opportunity before us for shaping new fields of knowledge, novel pedagogies and bringing back value to the oral and written wisdom generated in India over millennia, and at the same time, a meaningful future for it.”

Many of us experience the absurd disjunction I felt at the photocopy shop, between the education I was meant to imbibe and reality around me, in institutions of learning and at work-places. Yet we continue to participate in our narrow body of knowledge, preferring to stay in our ivory towers.

Devy, during his time in academia, sought to understand this difference. The conclusions he drew pulled him out of the university and took him to the edges of society. Devy has made some unusual choices: walking away from a lucrative career to travel through the countryside, creating a massive institution and then handing it over to the people, moving to a small town to seek justice for a man he did not know well. But for Devy, there is nothing saintlike about these preferences. Creative expansion is only possible at the edges, not at the comfortable centre.

Locating himself in Dharwad, then, makes complete sense. The fight for justice for Kalburgi, an outspoken Kannada scholar who was killed for challenging the political status quo, is now the frontline of the war over knowledge, language and politics. And Devy, who has spent his life taking on fundamental problems overlooked by the mainstream, is not one to shy away from a fight.

Devy was born in rural India, educated in a Marathi-medium school, and though he has spent time abroad, does not speak in an American or British accent. Most of the latter half of his life has been spent not in television studios, but travelling through obscure parts of the country. To an extent, he defies our preconceptions of who can be a public intellectual.

The clock struck five and a nearby mosque began broadcasting the evening azaan. We had been talking for over six hours, and Devy’s voice had grown hoarse. As we were about to wrap up, he said he had a question for me. “Do any of your friends or colleagues know the person or the subject you’re writing about?” he asked.

“Most of them don’t,” I told him. “There are several who have studied literature. But when I mentioned your name it was crickets.”

Devy laughed. “I’m not surprised,” he said.

First published by Caravan magazine