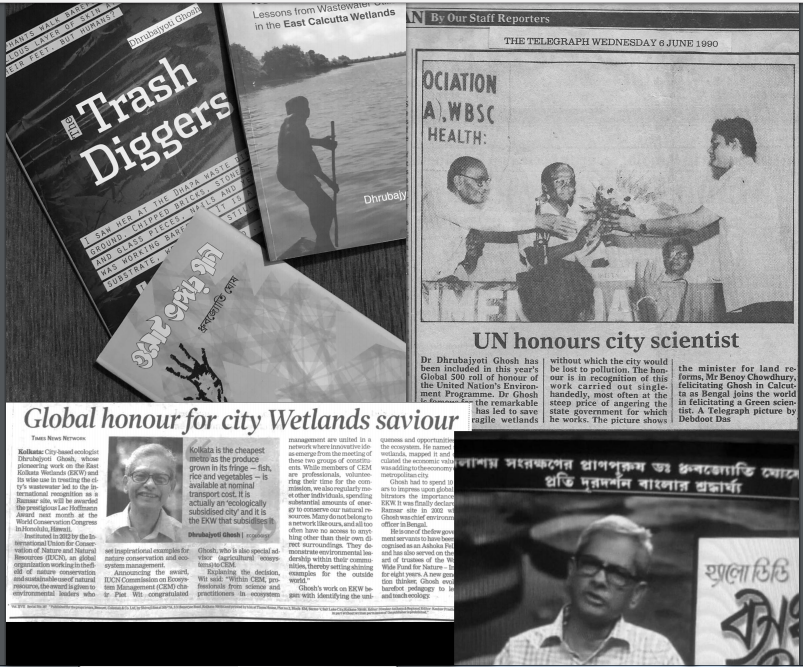

In the course of his work on the wetlands of East Kolkata Dhrubajyoti Ghosh published many articles in newspapers, magazines and academic journals. But he also published three significant volumes on ecology. The last of his three books, published by Oxford last year, is called The Trash Diggers. It is a pictorialised text on the lives and ecologically cleansing livelihoods of the ragpickers of the wetlands village called Dhapa. The villagers have been practising the environmental gospel of “reduce-reuse-recycle” for aeons without ever knowing the words. Urban recycling of non-biodegradable solid waste has been pioneered in India precisely by such officially illiterate, poor, semi-urban communities.

The Trash Diggers begins with the following Foreword by a villager from the wetlands:

“Mr. Ghosh has been visiting us for a very long time. I do not remember anyone else who has taken our photographs with such care and shown them when he came back. All his pictures describe our neighbourhood – how we live there, how we make a living, the types of fuel we use, how we eat, why there are holes in pigs’ ears. You do not know these things. If you see the pictures you will know. We are farmers on the Dhapa agricultural fields. But we also collect and separate the trash into different types, and then sell them to the traders for a little money. The plastics, glass, cloth, metals – all these that we collect are used to make many kinds of things. The vegetables we grow go to the markets. You buy them cheap. But no one talks about what will happen to us tomorrow. We live in constant fear about our future. If you look at these pictures, perhaps you too will think about us.”

These are the words of Soshthi Mandal who lives in Dhapa. He is the elder brother of Kalyani Mondal, a waste-picker who was crushed to death under a bulldozer on 20 February 2015, while working atop the Dhapa dump site. (“No one blinked”, writes Ghosh about her in his book). Over 5,000 families are engaged in the sorting and recycling of solid waste in Dhapa. They belong to ten different castes, sub-castes, and tribes and have come there both from other parts of West Bengal as well as from states nearby. They do not have a legal right to live and work there. Yet, their ecological contribution to the sustainability of the metropolis is huge, if invisible.

It was a Bengali entrepreneur, Bhabhanath Sen who first got a land lease from the colonial authorities in 1879 to grow vegetables atop the garbage heaps of Dhapa. Sen introduced the practice of co-recycling of solid waste and wastewater. The first urban garbage farmers in India worked in Dhapa. From the Dhapa experience of over a century, Ghosh concluded, and always insisted on, the twin principles of urban solid waste management: decentralised governance and managing waste as a resource.

“To what extent a community, a race, or a nation is civilised depends upon the waste it has to throw away”, writes Ghosh in The Trash Diggers. “The present dispensation is not just about the behavioural pattern of an excluded community. It is also about the kind of knowledge they have mastery upon and the science underneath.” In the theory of knowledge, Ghosh argued, there is growing respect for ‘tacit knowledge’ which presupposes a rational subject who is often unable to verbalise and narrate what s/he knows (almost like a soccer artist unable to give words to his skill).

However, this scarcely means that the knowledge lacks content. It is real, substantial, and positively consequential. It is derived from long and close experience of living and surviving successfully in a challenging ecological context like the East Kolkata Wetlands. The villagers have learned to be “adaptive and resilient” in tough conditions. In Ghosh’s words, “the Dhapa co-recycling practice sets a comprehensive example of a low-carbon model for city waste management that has not yet received the attention of those who matter.” (Something that should have merited public attention by now is the manner in which the natural wastewater recycling mechanism of the wetlands removes E.coli that cannot be cleaned by conventional sewage treatment plants even in advanced countries. It decomposes fruitfully in the tropical oxidation ponds of the Kolkata wetlands).

Ghosh was sarcastic about the manner in which the waste pickers of Dhapa are seen (more precisely rendered invisible) by municipal authorities and the metropolis at large. He wrote in his book: “A community that has been serving a metropolitan city with its painstaking practice of waste recycling, without recognition, remuneration, or social security, is a group that only merits the suspicion of being thieves and vandals! The beginning of this exclusion starts from the deliberate undercounting.” The waste pickers, mostly women, “remain unreachably beyond the notice of the average Kolkata citizen. That is the signature of our civility.” “We count the number of millionaires, but not the millions of pickers who are active in our nation’s backyards.”

Finally, these wetlands, like others known to ecologists, play a part in carbon recycling and sequestration. This last benefit is not to be taken lightly in a time of rapid deterioration in the world’s climate because of rising carbon emissions. Kolkata is the world’s third most exposed city, when it comes to the risk of climate flooding.

However, because these invaluable benefits of wetlands do not appear as cash in a ledger, they are brushed aside in the planning policies that allow developers to encroach and build there.

Ghosh’s intellectual contribution

In his book Ecosystem Management (NIMBY Books, 2014), Ghosh provocatively suggested that we scrutinise the ‘cognitive apartheid’ that stops experts, media, and the educated public from recognising the ecological wisdom of poor, illiterate communities who have so much to teach us. In making their livelihoods, these modest communities illustrate the ecological principle of self-organisation in ecosystems, with humans active and conscious agents and participants in their functioning. Only studied ecological ignorance can explain a public that takes no notice of this long-standing virtue, and builds luxury offices on fragile lands.

Ghosh also made a case that such ecologically wise communities actually have a ‘positive ecological footprint’. They take away very little from their environment and give back so much – unlike metropolitan households, offices and establishments that take so much and return only effluents. Globalised, metropolitan India is so accustomed to thinking of footprints as intrinsically negative that we fail to imagine that livelihoods can actually return more to nature than they take. It is possible. It happens. It may also happen to be the only way to live in the future.

Ghosh argued for the replacement of the dysfunctional ‘environmental impact assessment’ (“a bit of a joke”, in the words of a recent Union Minister of Environment, while he was still in office) by an ‘ecological assessment’ which would have as its foundation “a charter of ecological ethics”, with the renewable livelihoods of communities directly dependent on ecosystems as its primary reference point.

Ghosh insisted that human culture does not consist just of literature, cinema, music and dance. Rather, the patrimony of ecological culture, which is not just an artefact of the past, resides in the practical collective memory of communities, showing pathways of “living creatively with nature”. Such rooted wisdom lights up paths to an ecologically viable future for all of India, teeming as it is with communities who ‘know’ how to live in harmony with nature.

This is India’s epistemic gift, a privilege not available any more in the supposedly developed world. The ecological practices of people who live in intimacy with nature may be the key to the future survival of this civilisation.

Ghosh’s work of a lifetime has led to the birth of a new organisation, the Society for Creative Opportunities and Participatory Ecosystems (SCOPE), now managed by several of his students. It works, through research and action, to conserve the East Kolkata Wetlands, protecting them from the gluttonous claws of developers. In the face of stiff odds, Ghosh remains for them a steady light of inspiration.

(I wish to thank Dhruba Das Gupta of SCOPE for her suggestions).

First published by Modernama

Read Dhrubajyoti Ghosh, saviour of the East Kolkata Wetlands, believed in people and not policies