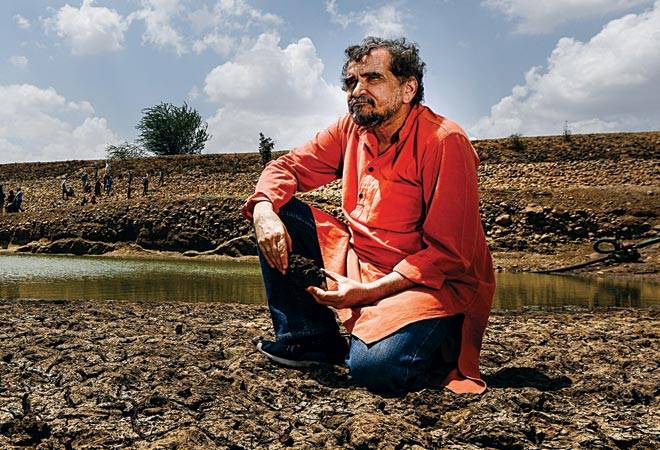

Mihir Shah, member, Planning Commission, says

The government, industry and the common man must recognise the common-pool-resource character of groundwater and be smart enough to realise that it is only by sharing it that we can all survive

If you want to really get smart with water, the first thing you should realise is that in most parts of India, water is abundantly available. But you also need to recall what a man named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi had once said: “There is enough in this world for everyone’s need, but not for anyone’s greed”. Today, what Gandhiji advised is being termed a “paradigm shift” in water management.

The basic idea is to move away from trying to augment water supply through construction and extraction and, instead, understand the centrality of managing what we have been blessed with, sustainably and equitably. This smart idea can solve our water problems and fundamentally change India by securing the lives and livelihoods of its people.

In the seven decades since Independence, we have spent Rs 4 lakh crore in building dams on our rivers. Despite that, we still face drought year after year. That is because after building a dam and canal systems (and displacing millions of people and submerging precious forests and farmland), we have forgotten to ensure this water reaches the farmers for whom it was originally meant.

We should be smart enough to get the farmers deeply involved in last-mile connectivity and managing water to bridge this gap. This is what countries across the world have done and so have some of our own states, which have empowered water users associations of farmers to charge irrigation service fees from their members, and use that money to operate and maintain the system.

The Centre also needs to incentivise and facilitate state governments to move towards participatory irrigation management (PIM). It should release funds for irrigation projects only on the condition that states will undertake these reforms. “No reform, no money,” is the smart way to go. A central committee on restructuring water governance in India in 2015 estimated that PIM could add 35 million hectares to irrigated areas over the next 10 years at Rs 1.5 lakh per hectare, compared to the present strategy of building more and more new dams that costs Rs 3 lakh-5 lakh per hectare – where the average cost over-run is as high as 1,382 per cent. PIM can not only help save land acquisition, resettlement and rehabilitation costs, but also avoid delays, cost escalation and bypass the politician-officer-contractor nexus. This would result in quick and enduring results.

India faces an even more serious crisis of mismanaging groundwater – the main source of water, accounting for 80 per cent domestic water consumption and two-thirds of agricultural use (farming comprises 80 per cent of India’s water use).

Indiscriminate tube-well drilling across India has also led to a man-made crisis for depleting water levels. In our hurry to extract groundwater, we have forgotten the basic principles of hydrogeology. We have overlooked the fact that nearly two-thirds of India is underlain by hard rock formations, which have a very low rate of groundwater recharge. Drilling deep into these rocks, we have literally mined groundwater, which took thousands of years to collect. As a result, what was originally a solution to the problem of water has now become a cause of the problem itself, with both water tables and water quality falling precipitously. Today we have arsenic, fluoride and even uranium in our drinking water, creating a serious health crisis.

Therefore, we must recognise the common pool resource (CPR) character of groundwater and be smart enough to realise that it is only by sharing it that we can all survive. As a member of Planning Commission, I had initiated a programme of aquifer mapping and management so that all stakeholders knew the exact boundaries of their aquifers, as also their storage capacity. Once they were provided this information, they were most likely to make smart decisions about groundwater use. The best example of this is a million farmers in the hard rock regions of Andhra Pradesh who came together to alter their cropping patterns (Mid-Term Appraisal of the Eleventh Five Year Plan, para 21.54), and engaged in smart crop-water budgeting to ensure that they could sustainably use their aquifers in an enduring fashion.

If we want to save India’s rivers, we must also be smart enough to look at surface and groundwater together. India’s peninsular rivers derive their post-monsoon flows from groundwater. The single most important factor explaining the drying up of these rivers is the over-extraction of groundwater in the catchments of these rivers. To rejuvenate our rivers, hydrologists, hydrogeologists, social mobilisers, ecologists, agronomists and primary stakeholders need to work together in every river basin.

The industry has also been responsible for India’s water woes. It has among the highest water footprints in the world. It must make every effort to utilise technologies readily available to reuse and recycle water. These technologies have incredibly low pay-back periods, making it in the enlightened self-interest of India’s corporate sector to adopt them.

Finally, India needs a complete relook at its flood management strategies that have overly relied on building dams and constructing embankments, which appear again to have only aggravated the problem. We again need to look for smart solutions. The world over, especially in chronically low-lying, flood-prone countries like the Netherlands, there has been a decisive move towards a ‘room for the river’ approach. We need to place far greater emphasis on rehabilitation of traditional, natural drainage systems, which would allow flood waters to navigate a safe passage through our towns and villages.

India’s water crisis has arisen out of a narrow construction-engineering-extraction-based approach to water. India needs to call for a new paradigm of water management based on the principles of multi-disciplinarity, people’s participation and balance. Since this requires massive social mobilisation, civil society organisations will need to work in close partnership with the government, industry and scientific research organisations for a truly smart move in water to become possible.

First published by Business Today