- The Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve in Sikkim, surrounding the world’s third highest peak Mount Khangchendzonga, has been added to UNESCO’s World Network of Biosphere Reserves, making it the 11th biosphere in India to be included in the network.

- Its location – bordering Nepal, Tibet (China) and in close proximity of Bhutan – offers unique opportunities for joint collaboration and conservation of biodiversity with neighbouring countries.

- The landscape is a testament of how religion, culture and environment protection can coexist harmoniously.

- Increasing unregulated tourism, lack of awareness about the landscape and shortage of staff are some of the key challenges in maintaining the reserve’s sanctity.

Tashi Wangdi, director and member secretary, Indian National MAB Committee of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, said the new designation broadens the possibility of engaging and co-operating with biosphere reserves in the MAB network internationally in order to look at conservation and development in a holistic manner.

“In the biosphere reserve, we have core, buffer and transition zones. The KNP is the core area in the KBR. It is a legal identity and under the Wildlife Protection Act. But the buffer and transition zones go hundreds of kilometres beyond the core area and that is where the challenge lies,” Wangdi told Mongabay-India.

As per UNESCO, the buffer zone adjoins the core area and is used for activities compatible with sound ecological practices that can reinforce scientific research, monitoring, training and education.

The transition area is the part of the reserve where the greatest activity is allowed, fostering economic and human development that is socio-culturally and ecologically sustainable.

About 35,000 people, mainly from the Lepcha, Bhutia, Nepalese and Limboo communities inhabit 44 villages in the areas surrounding the park.

“We have to work on how we can ease the pressure on the forest and natural resources and how we can improve the socio-economic status of the people in the area. They rely on the forest and natural resources for their livelihood so one area of work is extending alternative livelihood options so that pressure on natural resources can be minimised,” Wangdi said.

This apart, the WNBR widens the scope for better engagement of concerned ministry departments for troubleshooting as well for facilitating funds and resources for conservation work.

“In addition to that, we give importance to research and development activities so that we can find out gap areas in conservation, in development and in livelihood so they can be addressed,” Wangdi said.

Hemant K. Badola, advisor (biodiversity) in the office of Sikkim’s Chief Minister Pawan Chamling said the state is giving high priority to the conservation of landscape and importance to culture dissemination among masses.

“To regulate and monitor growing tourism over ecologically sensitive Himalayan zones and fragile terrains is a tough task. The organic landscape of Sikkim fascinates tourists. The Sikkim policies on tourism and ecotourism are clear manifestations on necessary measures, taking strong community participation,” Badola, told Mongabay-India.

Badola, the lead author of the UNESCO MAB nomination document of KBR stressed that the new inscription means the Sikkim government policies on promotion of ecotourism, organic farming and socio-economic development in the transition zone of KBR has proved “highly beneficial.”

The former scientist in-charge of the G.B. Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment & Sustainable Development (Sikkim) said it is also vital to understand that organic farming in transition zone of KBR has a great bearing upon enrichment of biodiversity in the area, said Badola,

“Worldwide, various scientific studies suggest the organic management in cropping help augmenting species richness and improved biodiversity. Over the years, evidences emerged that the organic farming in transition zone of KBR has resulted increasing soil fertility, better water absorption and abundance of pollinators, that helped vivid enhancement of biodiversity elements, both floral and faunal,” Badola added.

Changing perceptions

Occupying nearly 40 percent of the state, this biosphere reserve is one of the highest ecosystems in the world. Within an area of 2931 square km, the landscape slopes up from 1,220 to 8,586 metres.

Located in the Himalaya global biodiversity hotspot, KNP/KBR complex’s rugged and ancient terrain carpeted by old-growth forests draws birding and wildlife enthusiasts, pilgrims, rock climbers and star-gazers among others.

At Yuksom, a tranquil hamlet close to the entry of the KNP, friendly hosts, unhurried lifestyle and warm, inviting homestays that complete the rustic experience with traditional food are not only ensuring sustainable livelihood for the locals but also enabling them to protect and manage forests in accordance to the state’s ecotourism policy. Yuksom is the first capital of Sikkim.

Considered a pioneer in ecotourism in India, Yuksom-based NGO Khangchendzonga Conservation Committee (KCC), registered with the Sikkim government, helps locals run and manage homestays and also monitor impacts.

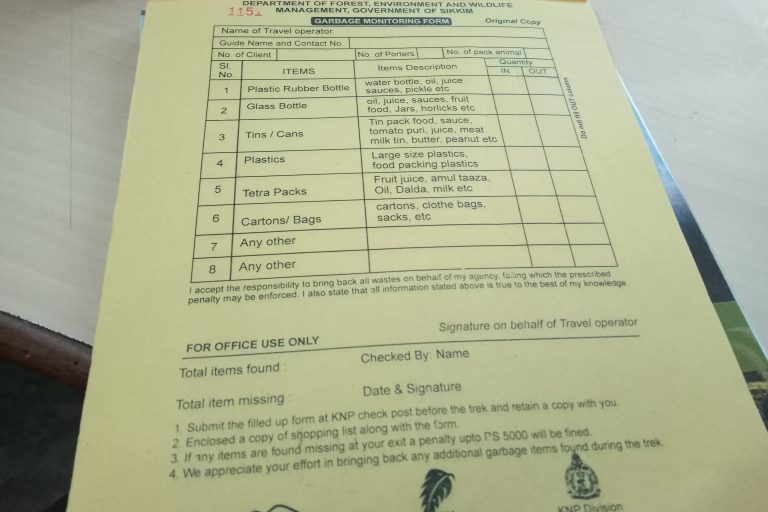

KCC has been assiduously monitoring the influx of trekkers and the items and waste they bring into the national park.

On their exit from the park, each item brought back is checked against those listed upon entry. If the items brought back are fewer than the ones taken in (implying littering inside the protected area) they are fined. Similarly, unauthorised extraction of medicinal plants and specimens including butterflies and moths is a strict no-no.

Locals opined more patrolling and monitoring staff is needed. In fact the KNP management plan discusses the shortage of trained staff to “protect some valuable medicinal plants of the park from illegal collectors and regular patrolling to check the cattle grazing within the park.”

Of late, the organisation’s Pema G. Bhutia revealed, travel companies bringing in large number of tourists at one go has become a cause for concern. He emphasised the importance of estimating the park’s carrying capacity: the number of people inside the park at one time.

“One aspect we are looking at is exploitation of the national park by some travel companies. We have certain travel companies who are promoting mass tourism bringing 40 to 50 people at one go. Following the UNESCO tag for the KNP we had hoped there would be studies and regulations in place regarding carrying capacity of the area. We hope that with the renewed focus, some steps can be taken,” Bhutia told Mongabay-India.

B.S. Siktel, the director of KBR agrees. “Poaching is no longer a major issue and biopiracy has diminished but tourism has gone up. We do not know the carrying capacity and no studies have been undertaken so far,” Siktel told Mongabay-India. “The landscape is a heaven for trekkers and pilgrims and ecotourism is a key money maker for the indigenous communities. While we recognise the importance of tourism, we also are aware of the pressures that mass tourism brings.”

Siktel pointed to the park’s management plan (2008-2018) that mentions the perils of unregulated tourism including damages to vegetation and change in the behavioural pattern of wild animals in general.

“Unregulated garbage dumping, un-designated camping sites and use of local timber wood for cooking pose a threat to the bio-resources of the park.”

Data provided by KCC shows the KNP received 457 tour groups and 289 international groups in 2012 while the numbers dropped to 150 (India) and 181 (international) in 2015 following the Nepal earthquake. 2016 witnessed an uptick to 261 (India) and 186 (international).

But numbers are just one side of the coin.

One of the key tenets of ecotourism practised at Yuksom is interaction between hosts and guests. According to Uden from KCC, this interaction (a casual chat over a bonfire, or on a jungle trek) is aimed to apprise visitors of the importance of the landscape and culture. The more they learn, the less chances there are for any inadvertent harm to the place.

But many private hoteliers and fly-by-night operators disregard the education part of the deal.

“So guests do not learn to value the landscape. Moreover, the benefits from ecotourism do not come to the community,” Uden said. “ Our model of ecotourism relies on travellers viewing the landscape with respect and this attitude triggers positive actions such as not disposing any waste in the trek. This helps us in conservation.”

To drive home the point on awareness, KCC’s Bhutia cites the example of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, popularly called the “toy train”, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“The kind of joy and pride that one experiences while riding the Darjeeling toy train, similar pride and joy should be felt by visitors to KNP/KBR landscape. Instead of thinking that one is traveling to one of those national parks, they should feel the difference in understanding that KNP is special. We need to work hard and create awareness in this regard,” Bhutia stressed.

Diminishing use of Lepcha, Bhutia and Nepali languages, the changing character of traditional villages and questions about the cultural appropriateness of tourist-town “nightlife” are listed in the management plan as some of the apprehensions regarding impacts of tourism.

As per the plan: “At the heart of all these concerns is a perceived loss of Lepcha, Bhutia and Nepali identity in the own homeland and a wish to maintain styles of tourism that are appropriate to the national park and cultural context.”

Braiding conservation with traditional knowledge

The Khangchendzonga landscape, of which the Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve (KBR), with Khangchendzonga National Park as its core area, is a major part, shared between Bhutan, India and Nepal.

Badola stressed on the importance of linking human-centric biodiversity conservation to the transboundary nature of the Khangchendzonga landscape.

“The endurance of the landscape is evidence of the fact that biocultural knowledge from local people can bring protection and biodiversity conservation benefits to a region,” Badola, also the former nodal scientist for the Khangchendzonga Landscape, Indian part, explained.

Biocultural knowledge denotes interconnectivity between human behaviour and biodiversity.

Having lived in Sikkim for over two decades, the state’s chief wildlife warden C.S. Rao attests to the fact it is due to the reverence towards Mt. Khangchendzonga that retaliatory killings are unheard of, despite incidences of crop depredation by animals in the region.

Badola highlighted the harnessing of medicinal plants as an example of preservation and continuation of biocultural knowledge. For example, Lepcha tribe traditionally use 118 medicinal plant species (targeting 66 ailments) and the Limbu tribe use 124 plants (curing 77 ailments).

This knowledge is the secret of how communities have responded and adapted to various environmental changes in the context of climate change and globalisation, he added.

First published by Mongabay